…as Oscar Wilde well might have titled an essay about campus-wide IT, had there been such a thing back then.

Enterprise IT it accounts for the lion’s share of campus IT staffing, expenditure, and risk. Yet it receives curiously little attention in national discussion of IT’s strategic higher-education role. Perhaps that should change. Two questions arise:

- What does “Enterprise” mean within higher-education IT?

- Why might the importance of Enterprise IT evolve?

What does “Enterprise IT” mean?

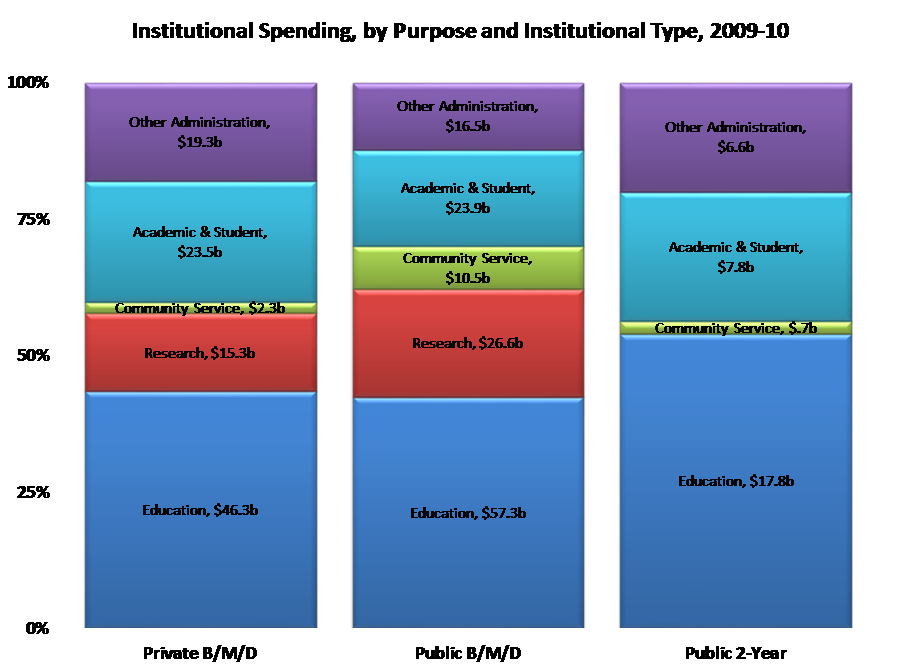

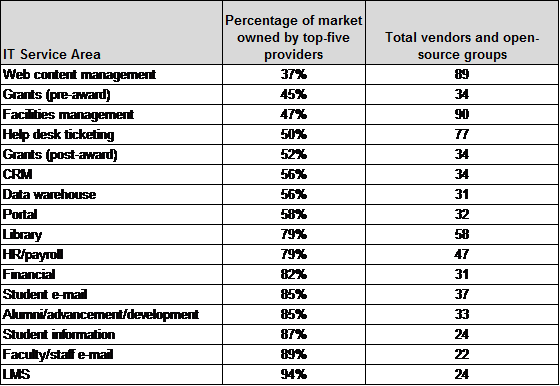

Here are some higher-education spending data from the federal Integrated Postsecondary Education Data Service (IPEDS), omitting hospitals, auxiliaries, and the like:

Broadly speaking, colleges and universities deploy resources with goals and purposes that relate to their substantive mission or the underlying instrumental infrastructure and administration.

- Substantive purposes and goals comprise some combination of education, research, and community service. These correspond to the bottom three categories in the IPEDS graph above. Few institutions focus predominantly on research—Rockefeller University, for example. Most research universities pursue all three missions, most community colleges emphasize the first and third, and most liberal-arts colleges focus on the first.

- Instrumental activities are those that equip, organize, and administer colleges and universities for optimal progress toward their mission—the top two categories in the IPEDS graph. In some cases, core activities advance institutional mission by providing a common infrastructure for the latter. In other cases, they do it by providing campus-wide or departmental staffing, management, and processes to expedite mission-oriented work. In still other cases, they do it through collaboration with other institutions or by contracting for outside services.

Education, research, and community service all use IT substantively to some extent. This includes technologies that directly or indirectly serve teaching and learning, technologies that directly enable research, and technologies that provide information and services to outside communities—for examples of all three, classroom technologies, learning management systems, technologies tailored to specific research data collection or analysis, research data repositories, library systems, and so forth.

Instrumental functions rely much more heavily on IT. Administrative processes rely increasingly on IT-based automation, standardization, and outsourcing. Mission-oriented IT applications share core infrastructure, services, and support. Core IT includes infrastructure such as networks and data centers, storage and computational clouds, and desktop and mobile devices; administrative systems ranging from financial, HR, student-record, and other back office systems to learning-management and library systems; and communications, messaging, collaboration, and social-media systems.

In a sense, then, there are six technology domains within college and university IT:

- the three substantive domains (education, research, and community service), and

- the three instrumental domains (infrastructure, administration, and communications).

Especially in the instrumental domains, “IT” includes not only technology, but also the services, support, and staffing associated with it. Each domain therefore has technology, service, support, and strategic components.

Based on this, here is a working definition: in in higher education,

“Enterprise” IT comprises the IT-related infrastructure, applications, services, and staff

whose primary institutional role is instrumental rather than substantive.

Exploring Enterprise IT, framed thus, entails focusing on technology, services, and support as they relate to campus IT infrastructure, administrative systems, and communications mechanisms, plus their strategic, management, and policy contexts.

Why Might the Importance of Enterprise IT Evolve?

Three reasons: magnitude, change, and overlap.

Magnitude

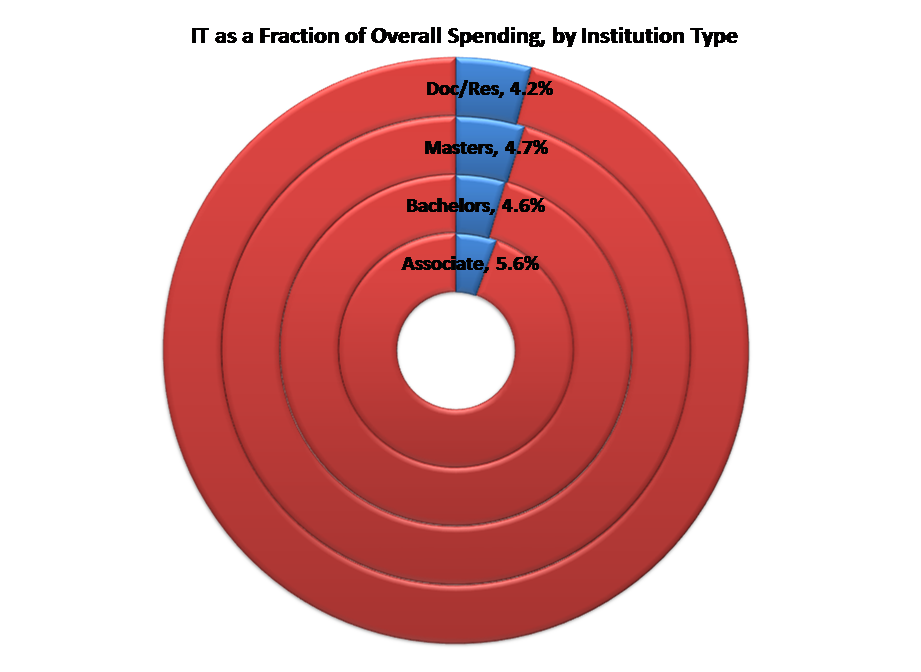

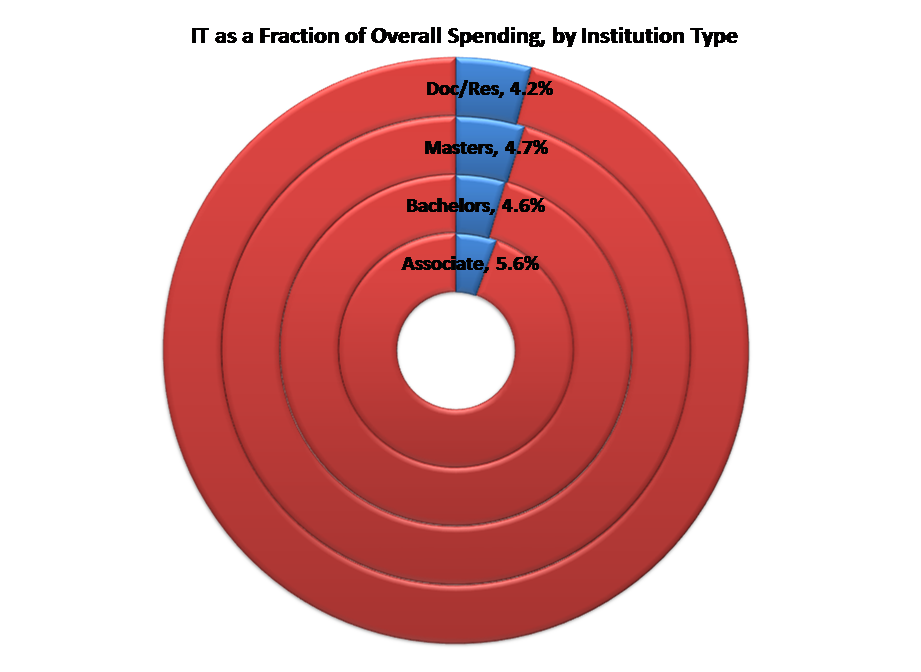

According data from EDUCAUSE’s Core Data Service (CDS) and the federal Integrated Postsecondary Data System (IPEDS), the typical college or university spends just shy of 5% of its operating budget on IT. This varies a bit across institutional types:

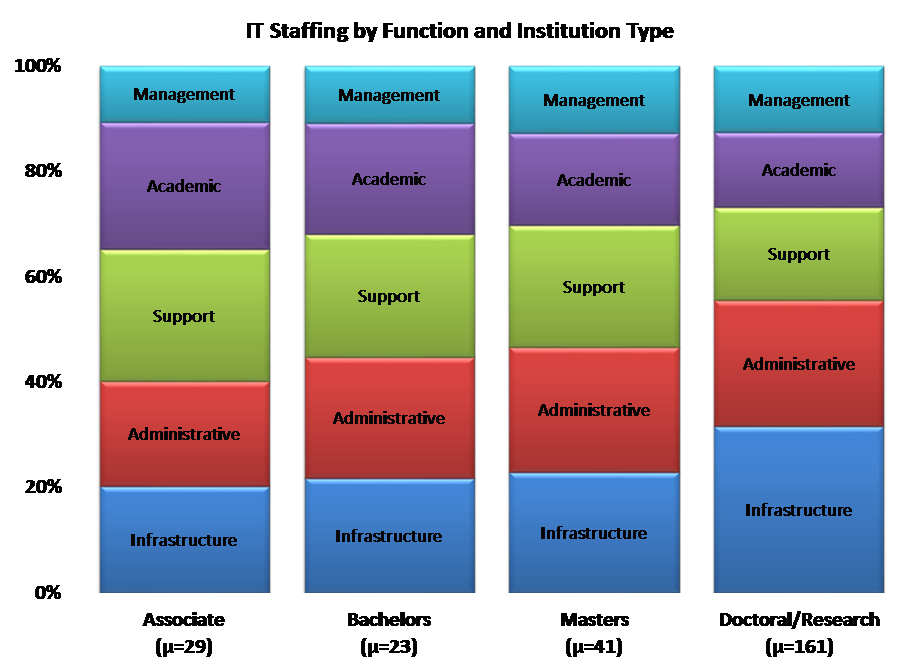

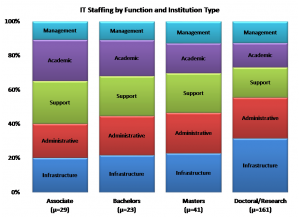

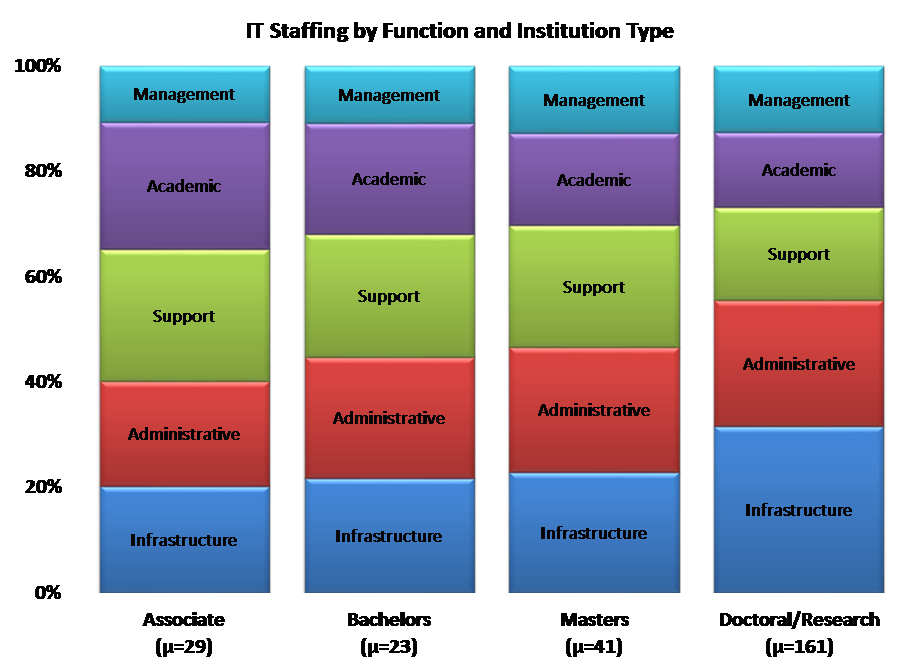

We lack good data breaking down IT expenditures further. However, we do have CDS data on how IT staff distribute across different IT functions. Here is a summary graph, combining education and research into “academic” (community service accounts for very little dedicated IT effort):

Thus my assertion above that Enterprise IT accounts for the lion’s share of IT staffing. Even if we omit the “Management” component, Enterprise IT comprises 60-70% of staffing including IT support, almost half without. The distribution is even more skewed for expenditure, since hardware, applications, services, and maintenance are disproportionately greater in Administration and Infrastructure.

Why, given the magnitude of Enterprise relative to other college and university IT, has it not been more prominent in strategic discussion? There are at least two explanations:

- relatively slow change in Enterprise IT, at least compared to other IT domains (rapidly-changing domains rightly receive more attention that stable ones), and

- overlap—if not competition—between higher-education and vendor initiatives in the Enterprise space.

Change

Enterprise IT is changing thematically, driven by mobility, cloud, and other fundamental changes in information technology. It also is changing specifically, as concrete challenges arise.

Consider, as one way to approach the former, these five thematic metamorphoses:

- In systems and applications, maintenance is giving way to renewal. At one time colleges and universities developed their own administrative systems, equipped their own data centers, and deployed their own networks. In-house development has given way to outside products and services installed and managed on campus, and more recently to the same products and services delivered in or from the cloud.

- In procurement and deployment, direct administration and operations are giving way to negotiation with outside providers and oversight of the resulting services. Whereas once IT staff needed to have intricate knowledge of how systems worked, today that can be less useful that effective negotiation, monitoring, and mediation.

- In data stewardship and archiving, segregated data and systems are giving way to integrated warehouses and tools. Historical data used to remain within administrative systems. The cost of keeping them “live” became too high, and so they moved to cheaper, less flexible, and even more compartmentalized media. The plunging price of storage and the emergence of sophisticated data warehouses and business-intelligence systems reversed this. Over time, storage-based barriers to data integration have gradually fallen.

- In management support, unidimensional reporting is giving way to multivariate analytics. Where once summary statistics emerged separately from different business domains, and drawing inferences about their interconnections required administrative experience and intuition, today connections can be made at the record level deep within integrated data warehouses. Speculating about relationships between trends is giving way to exploring the implications of documented correlations.

- In user support, authority is giving way to persuasion. Where once users had to accept institutional choices if they wanted IT support, today they choose their own devices, expect campus IT organizations to support them, and bypass central systems if support is not forthcoming. To maintain the security and integrity of core systems, IT staff can no longer simply require that users behave appropriately; rather, they must persuade users to do so. This means that IT staff increasingly become advocates rather than controllers. The required skillsets, processes, and administrative structures have been changing accordingly.

Beyond these broad thematic changes, a fourfold confluence is about to accelerate change in Enterprise IT: major systems approaching end-of-life, the growing importance of analytics, extensive mobility supported by third parties, and the availability of affordable, capable cloud-based infrastructure, services, and applications.

Systems Approaching End-of-Life

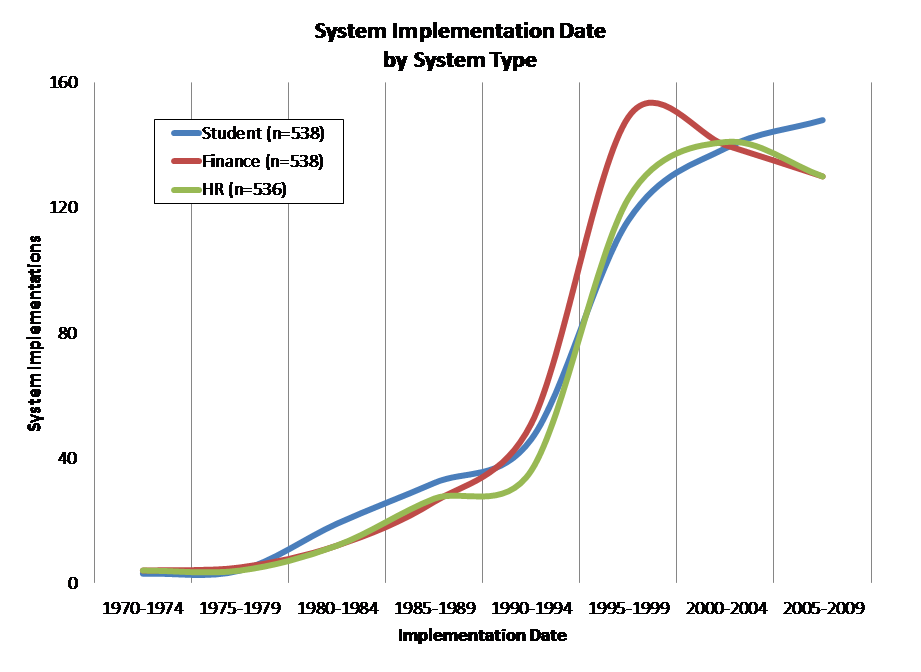

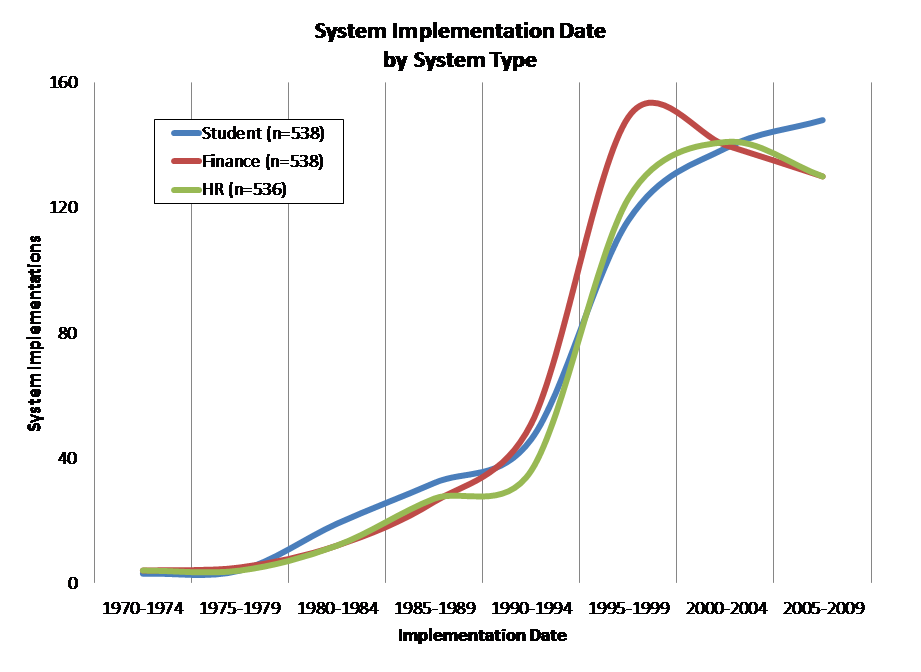

In the mid-1990s, many colleges and universities invested heavily in administrative-systems suites, often (if inaccurately) called “Enterprise Reporting and Planning” systems or “ERP.” Here, again drawing on CDS, are implementation data on Student, Finance, and HR/Payroll systems for non-specialized colleges and universities:

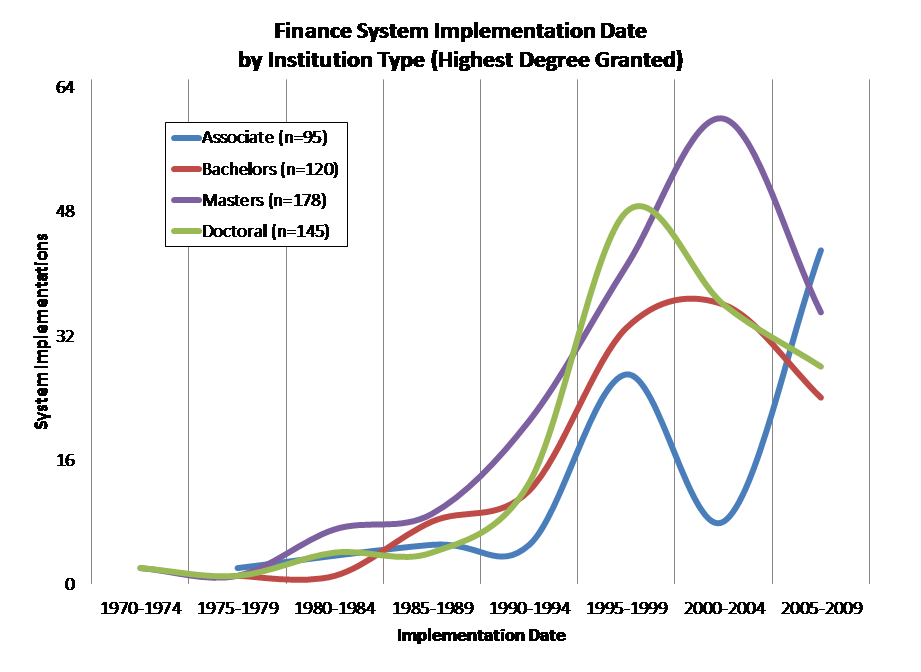

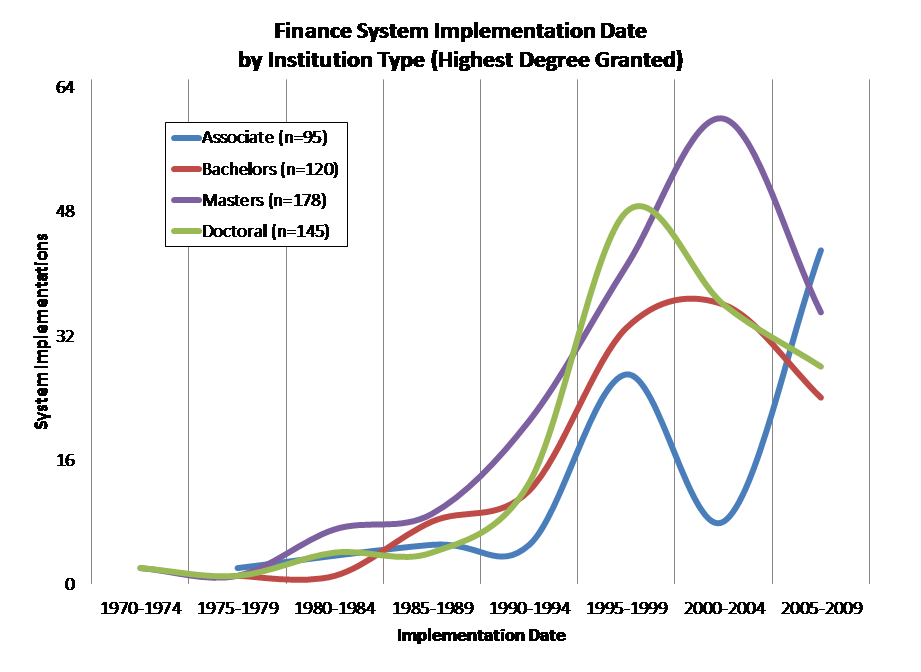

The pattern of implementation varies slightly across institution types. Here, for example, are implementation dates for Finance systems across four broad college and university groups:

Although these systems have generally been updated regularly since they were implemented, they are approaching the end of their functional life. That is, although they technically can operate into the future, the functionality of turn-of-the-century administrative systems likely falls short of what institutions currently require. Such functional obsolescence typically happens after about 20 years.

The general point holds across higher education: A great many administrative systems will reach their 20-year anniversaries over the next several years.

Moreover, many commercial administrative-systems providers end support for older products, even if those products have been maintained and updated. This typically happens as new products with different functionality and/or architecture establish themselves in the market.

These two milestones—functional obsolescence and loss of vendor support—mean that many institutions will be considering restructuring or replacement of their core administrative systems over the next few years. This, in turn, means that administrative-systems stability will give way to 1990s-style uncertainty and change.

Growing Importance of Analytics

Partly as a result of mid-1990s systems replacements, institutions have accumulated extensive historical data from their operations. They have complemented and integrated these by implementing flexible data-warehousing and business-intelligence systems.

Over the past decade, the increasing availability of sophisticated data-mining tools has given new purpose to data warehouses and business-intelligence systems that have until now have largely provided simple reports. This has laid foundation for the explosive growth of analytic management approaches (if, for the present, more rhetorical than real) in colleges and universities, and in the state and federal agencies that fund and/or regulate them.

As analytics become prominent in areas ranging from administrative planning to student feedback, administrative systems need to become better integrated across organizational units and data sources. The resulting datasets need to become much more widely accessible while complying with privacy requirements. Neither of these is easy to achieve. Achieving them together is more difficult still.

Mobility Supported by Third Parties

Until about five years ago campus communications—infrastructure and services both—were largely provided and controlled by institutions. This is no longer the case.

Much networking has moved from campus-provided wired and WiFi facilities to cellular and other connectivity provided by third parties, largely because those third parties also provide the mobile end-user devices students, faculty, and staff favor.

Separately, campus-provided email and collaboration systems have given way to “free” third-party email, productivity, and social-media services funded by advertising rather than institutional revenue. That mobile devices and their networking are largely outside campus control is triggering fundamental rethinking of instruction, assessment, identity, access, and security processes. This rethinking, in turn, is triggering re-engineering of core systems.

Affordable, Capable Cloud

Colleges and universities have long owned and managed IT themselves, based on two assumptions: that campus infrastructure needs are so idiosyncratic that they can only be satisfied internally, and that campuses are more sophisticated technologically than other organizations.

Both assumptions held well into the 1990s. That has changed. “Outside” technology has caught up to and surpassed campus technology, and campuses have gradually recognized and begun to avoid the costs of idiosyncrasy.

As a result, outside services ranging from commercially hosted applications to cloud infrastructure are rapidly supplanting campus-hosted services. This has profound implications for IT staffing—both levels and skillsets.

The upshot is that Enterprise, already the largest component of higher-education IT, is entering a period of dramatic change.

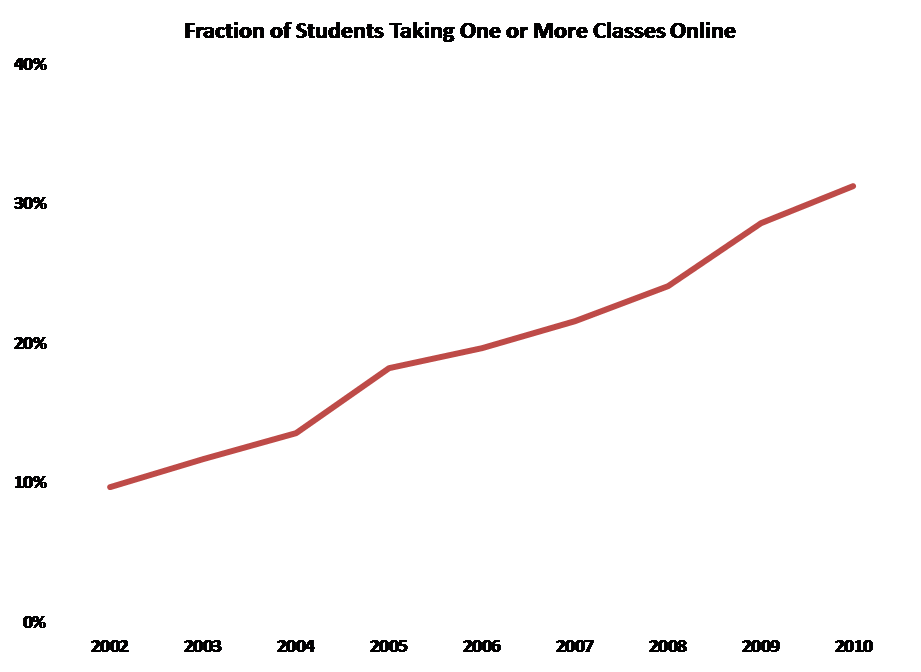

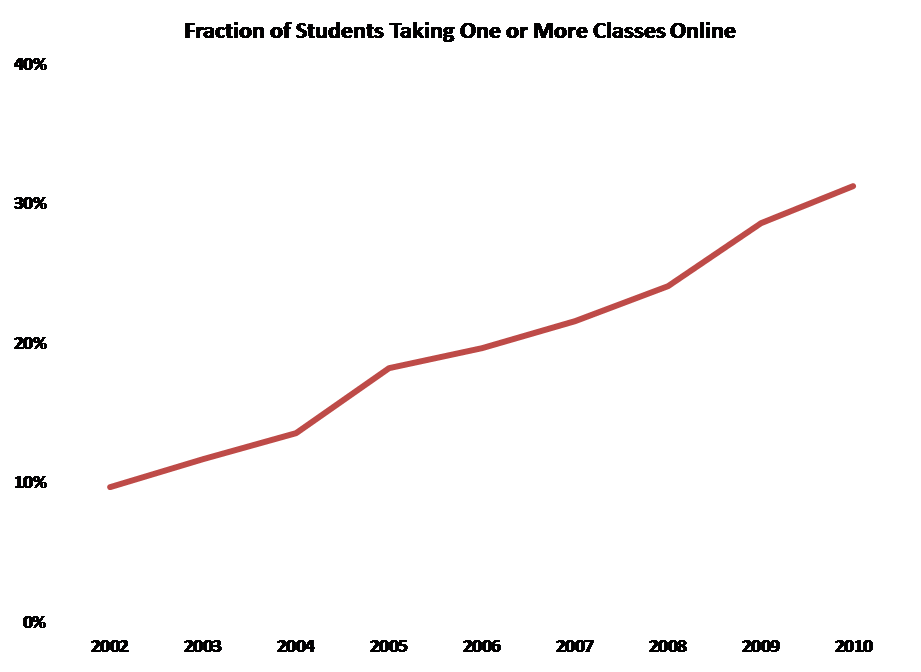

Beyond change in IT, the academy itself is evolving dramatically. For example, online enrollment is becoming increasingly common. As the Sloan Foundation reports, the fraction of students taking some or all of their coursework online is increasing steadily:

This has implications not only for pedagogy and learning environments, but also for the infrastructure and applications necessary to serve remote and mobile students.

Changes in the IT and academic enterprises are one reason Enterprise IT needs more attention. A second is the panoply of entities that try to influence Enterprise IT.

Overlap

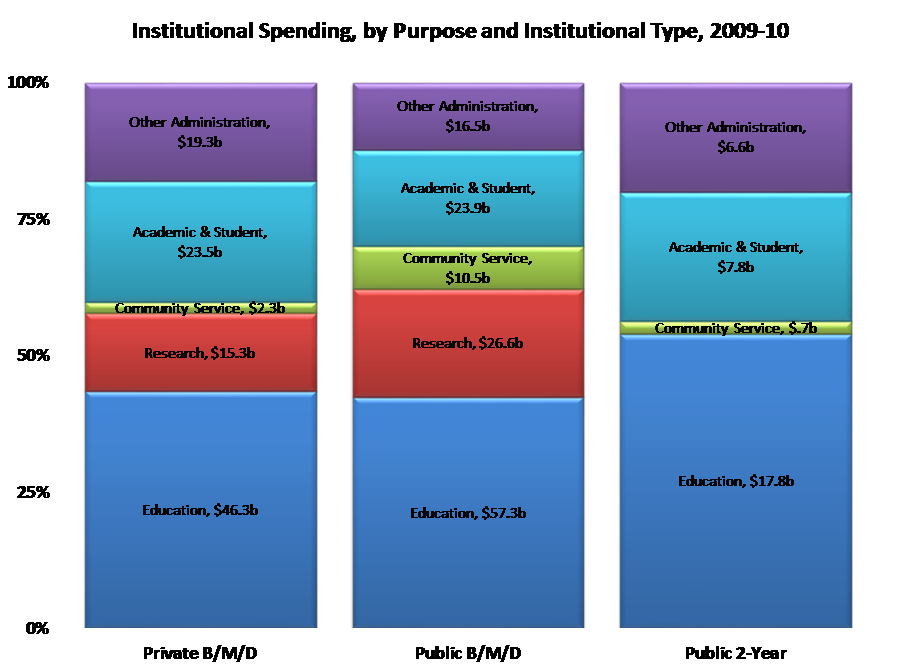

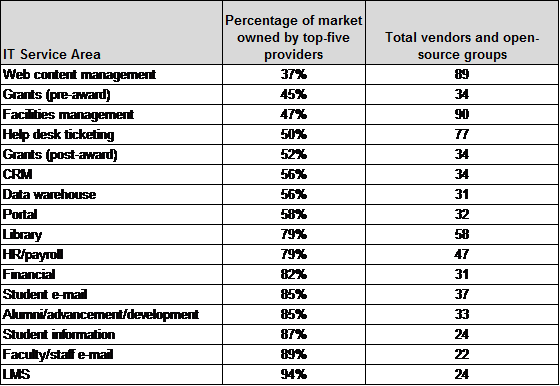

One might expect colleges and universities to have relatively consistent requirements for administrative systems, and therefore that the market for those would consist largely of a few major widely-used products. The facts are otherwise. Here are data from the recent EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research (ECAR) research report The 2011 Enterprise Application Market in Higher Education:

The closest we come to a compact market is for learning management systems, where 94% of installed systems come from the top 5 vendors. Even in this area, however, there are 24 vendors and open-source groups. At the other extreme is web content management, where 89 active companies and groups compete and the top providers account for just over a third of the market.

One way major vendors compete under circumstances like these is by seeking entrée into the informal networks through which institutions share information and experiences. They do this, in many cases, by inviting campus CIOs or administrative-systems heads to join advisory groups or participate in vendor-sponsored conferences.

That these groups are usually more about promoting product than seeking strategic or technical advice is clear. They are typically hosted and managed by corporate marketing groups, not technical groups. In some cases the advisory groups comprise only a few members, in some cases they are quite large, and in a few cases there are various advisory tiers. CIOs from large colleges and universities are often invited to various such groups. For the most part these groups have very little effect on vendor marketing, and even less on technical architecture and direction.

So why do CIOs attend corporate advisory board meetings? The value to CIOs, aside from getting to know marketing heads, is that these groups’ meetings provide a venue for engaging enterprise issues with peers. The problem is that the number of meetings and their oddly overlapping memberships lead to scattershot conversations inevitably colored by the hosts’ marketing goals and technical choices. It is neither efficient nor effective for higher education to let vendors control discussions of Enterprise IT.

Before corporate advisory bodies became so prevalent, there were groups within higher-education IT that focused on Enterprise IT and especially on administrative systems and network infrastructure. Starting with 1950s workshops on the use of punch cards in higher education, CUMREC hosted meetings and publications focused on the business use of information technology. CAUSE emerged from CUMREC in the late 1960s, and remained focused on administrative systems. EDUCOM came into existence in the mid-1960s, and its focus evolved to complement those of CAUSE and CUMREC by addressing joint procurement, networking, academic technologies, copyright, and in general taking a broad, inclusive approach to IT. Within EDUCOM, the Net@EDU initiative focused on networking much the way CUMREC focused on business systems.

As these various groups melded into a few larger entities, especially EDUCAUSE, Enterprise IT remained a focus, but it was only one of many. Especially as the y2k challenge prompted increased attention to administrative systems and intensive communications demands prompted major investments in networking, the prominence of Enterprise IT issues in collective work diffused further. Internet2 became the focal point for networking engagements, and corporate advisory groups became the focal point for administrative-systems engagements. More recently, entities such as Gartner, the Chronicle of Higher Education, and edu1world have tried to become influential in the Enterprise IT space.

The results of the overlap among vendor groups and associations, unfortunately, are scattershot attention and dissipated energy in the higher-education Enterprise IT space. Neither serves higher education well. Overlap thus joins accelerated change as a major argument for refocusing and reenergizing Enterprise IT.

The Importance of Enterprise IT

Enterprise IT, through its emphasis on core institutional activities, is central to the success of higher education. Yet the community’s work in the domain has yet to coalesce into an effective whole. Perhaps this is because we have been extremely respectful of divergent traditions, communities, and past achievements.

We must not be disrespectful, but it is time to change this: to focus explicitly on what Enterprise IT needs in order to continue advancing higher education, to recognize its strategic importance, and to restore its prominence.

9/25/12 gj-a

On the informal agenda, a bunch of us work behind the scenes trying to persuade two existing higher-education IT entities–Internet2 and National LambdaRail–that they would better serve their constituencies, which overlap but do not coincide, by consolidating into a single organization.

On the informal agenda, a bunch of us work behind the scenes trying to persuade two existing higher-education IT entities–Internet2 and National LambdaRail–that they would better serve their constituencies, which overlap but do not coincide, by consolidating into a single organization.

Most everyone appears to agree that having two competing national networking organizations for higher education wastes scarce resources and constrains progress. But both NLR and Internet2 want to run the consolidated entity. Also, there are some personalities involved. Our work behind the scenes is mostly shuttle diplomacy involving successively more complex drafts of charter and bylaws for a merged networking entity.

Most everyone appears to agree that having two competing national networking organizations for higher education wastes scarce resources and constrains progress. But both NLR and Internet2 want to run the consolidated entity. Also, there are some personalities involved. Our work behind the scenes is mostly shuttle diplomacy involving successively more complex drafts of charter and bylaws for a merged networking entity.![]()

Partly I’m wistfully remembering the long and somewhat similar courtship between CAUSE and Educom, which eventually yielded today’s merged EDUCAUSE. I’m hoping that we’ll be able to achieve something similar for national higher-education networking.

Partly I’m wistfully remembering the long and somewhat similar courtship between CAUSE and Educom, which eventually yielded today’s merged EDUCAUSE. I’m hoping that we’ll be able to achieve something similar for national higher-education networking. And partly I’m remembering a counterexample, the demise of the American Association for Higher Education, which for years held its annual meeting at the Hilton adjacent to Grant Park in Chicago (almost always overlapping my birthday, for some reason). AAHE was an umbrella organization aimed comprehensively at leaders and middle managers throughout higher education, rather than at specific subgroups such as registrars, CFOs, admissions directors, housing managers, CIOs, and so forth. It also attracted higher-education researchers, which is how I started attending, since that’s what I was.

And partly I’m remembering a counterexample, the demise of the American Association for Higher Education, which for years held its annual meeting at the Hilton adjacent to Grant Park in Chicago (almost always overlapping my birthday, for some reason). AAHE was an umbrella organization aimed comprehensively at leaders and middle managers throughout higher education, rather than at specific subgroups such as registrars, CFOs, admissions directors, housing managers, CIOs, and so forth. It also attracted higher-education researchers, which is how I started attending, since that’s what I was.![]() Together the split into caucuses and over-trendiness left AAHE with no viable general constituency or finances to continue its annual meetings, its support for Change magazine, or its other crosscutting efforts. AAHE shut down in 2005, and disappeared so thoroughly that it doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page; its only online organizational existence is at the Hoover Institution’s archives, which hold its papers.

Together the split into caucuses and over-trendiness left AAHE with no viable general constituency or finances to continue its annual meetings, its support for Change magazine, or its other crosscutting efforts. AAHE shut down in 2005, and disappeared so thoroughly that it doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page; its only online organizational existence is at the Hoover Institution’s archives, which hold its papers. At the Duke CSG meeting I’m hoping, as we work on I2 and NLR leaders to encourage convergence, that NLR v. I2 won’t turn out like AAHE, and that instead the two organizations will agree to a collaborative process leading to synergy and merger like that of CAUSE and Educom.

At the Duke CSG meeting I’m hoping, as we work on I2 and NLR leaders to encourage convergence, that NLR v. I2 won’t turn out like AAHE, and that instead the two organizations will agree to a collaborative process leading to synergy and merger like that of CAUSE and Educom. Following the Duke CSG meeting, NLR and I2 continue to compete. They manage to collaborate briefly on a joint proposal for federal funding, a project called “U.S. UCAN“, but then that collaboration falls apart as NLR’s finances weaken. Internet2 commits to cover NLR’s share of U.S. UCAN, an unexpected burden. NLR hires a new CEO to turn things around; he leaves after less than a year. NLR looks to the private sector for funding, and finds some, but it’s not enough: its network shuts down abruptly in 2014.

Following the Duke CSG meeting, NLR and I2 continue to compete. They manage to collaborate briefly on a joint proposal for federal funding, a project called “U.S. UCAN“, but then that collaboration falls apart as NLR’s finances weaken. Internet2 commits to cover NLR’s share of U.S. UCAN, an unexpected burden. NLR hires a new CEO to turn things around; he leaves after less than a year. NLR looks to the private sector for funding, and finds some, but it’s not enough: its network shuts down abruptly in 2014.![]() Meanwhile, despite some false starts and missed opportunities, the EDUCAUSE merger succeeds. The organization grows and modernizes. It tackles a broad array of services to and advocacy on behalf of higher-education IT interests, organizations, and staff.

Meanwhile, despite some false starts and missed opportunities, the EDUCAUSE merger succeeds. The organization grows and modernizes. It tackles a broad array of services to and advocacy on behalf of higher-education IT interests, organizations, and staff.![]() Partly the issue is simple organizational management efficiency: in these times of tight resources for colleges, universities, and state systems, does higher education IT really need two financial staffs, two membership-service desks, two marketing/communications groups, two senior leadership teams, two Boards, and for that matter two CEOs? (Throw ACUTA, Unizin, Apereo, and other entities into the mix, and the question becomes even more pressing.)

Partly the issue is simple organizational management efficiency: in these times of tight resources for colleges, universities, and state systems, does higher education IT really need two financial staffs, two membership-service desks, two marketing/communications groups, two senior leadership teams, two Boards, and for that matter two CEOs? (Throw ACUTA, Unizin, Apereo, and other entities into the mix, and the question becomes even more pressing.) But partly the issue is deeper. EDUCAUSE and Internet2 are beginning to compete with one another for scarce resources in subtle ways: dues and memberships, certainly, but also member allegiance, outside funding, and national roles. That competition, if it grows, seems perilous. More worrisome still, some of the competition is of the non-salutary I’m OK/You’re Not OK variety, whereby each organization thinks the other should be subservient.

But partly the issue is deeper. EDUCAUSE and Internet2 are beginning to compete with one another for scarce resources in subtle ways: dues and memberships, certainly, but also member allegiance, outside funding, and national roles. That competition, if it grows, seems perilous. More worrisome still, some of the competition is of the non-salutary I’m OK/You’re Not OK variety, whereby each organization thinks the other should be subservient. We don’t quite have a Timson/Molloy situation, I’m glad to say. But with little productive interaction at the organizations’ senior levels to build effective, equitable collaboration, there’s unnecessary risk that competitive tensions will evolve into feudal isolation.

We don’t quite have a Timson/Molloy situation, I’m glad to say. But with little productive interaction at the organizations’ senior levels to build effective, equitable collaboration, there’s unnecessary risk that competitive tensions will evolve into feudal isolation.

The last time

The last time  The word “transmit” is important, because it’s different from “send” and “receive”. Users connect computers, servers, phones, television sets, and other devices to networks. They choose and pay for the capacity of their connection (the “pipe”, in the usual but imperfect plumbing analogy) to send and receive network traffic. Not all pipes are the same, and it’s perfectly acceptable for a network to provide lower-quality pipes–slower, for example–to end users who pay less, and to charge customers differently depending on where they are located. But a neutral network must provide the same quality of service to those who pay for the same size, quality, and location of “pipe”.

The word “transmit” is important, because it’s different from “send” and “receive”. Users connect computers, servers, phones, television sets, and other devices to networks. They choose and pay for the capacity of their connection (the “pipe”, in the usual but imperfect plumbing analogy) to send and receive network traffic. Not all pipes are the same, and it’s perfectly acceptable for a network to provide lower-quality pipes–slower, for example–to end users who pay less, and to charge customers differently depending on where they are located. But a neutral network must provide the same quality of service to those who pay for the same size, quality, and location of “pipe”. s also important to consider two different (although sometimes overlapping) kinds of users: “end users” and “providers”. In general, providers deliver services to end users, sometimes content (for example, Netflix, the New York Times, or Google Search), sometimes storage (OneDrive, Dropbox), sometimes communications (Gmail, Xfinity Connect), and sometimes combinations of these and other functionality (Office Online, Google Apps).

s also important to consider two different (although sometimes overlapping) kinds of users: “end users” and “providers”. In general, providers deliver services to end users, sometimes content (for example, Netflix, the New York Times, or Google Search), sometimes storage (OneDrive, Dropbox), sometimes communications (Gmail, Xfinity Connect), and sometimes combinations of these and other functionality (Office Online, Google Apps). Networks (and therefore network operators) can play different roles in transmission: “first mile”, “last mile”, “backbone”, and “peering”. Providers connect to first-mile networks. End users do the same to last-mile networks. (First-mile and last-mile networks are mirror images of each other, of course, and can swap roles, but there’s always one of each for any traffic.) Sometimes first-mile networks connect directly to last-mile networks, and sometimes they interconnect indirectly using backbones, which in turn can interconnect with other backbones. Peering is how first-mile, last-mile, and backbone networks interconnect.

Networks (and therefore network operators) can play different roles in transmission: “first mile”, “last mile”, “backbone”, and “peering”. Providers connect to first-mile networks. End users do the same to last-mile networks. (First-mile and last-mile networks are mirror images of each other, of course, and can swap roles, but there’s always one of each for any traffic.) Sometimes first-mile networks connect directly to last-mile networks, and sometimes they interconnect indirectly using backbones, which in turn can interconnect with other backbones. Peering is how first-mile, last-mile, and backbone networks interconnect. Consider how I connect the Mac on my desk in

Consider how I connect the Mac on my desk in  “Public” networks are treated differently than “private” ones. Generally speaking, if a network is open to the general public, and charges them fees to use it, then it’s a public network. If access is mostly restricted to a defined, closed community and does not charge use fees, then it’s a private network. The distinction between public and private networks comes mostly from the

“Public” networks are treated differently than “private” ones. Generally speaking, if a network is open to the general public, and charges them fees to use it, then it’s a public network. If access is mostly restricted to a defined, closed community and does not charge use fees, then it’s a private network. The distinction between public and private networks comes mostly from the  Most campus networks are private by this definition. So are my home network, the network here in the DC Comcast office, and the one in my local Starbucks. To take the roadway analogy a step further, home driveways, the extensive network of roads within gated residential communities (even a large one such as

Most campus networks are private by this definition. So are my home network, the network here in the DC Comcast office, and the one in my local Starbucks. To take the roadway analogy a step further, home driveways, the extensive network of roads within gated residential communities (even a large one such as  An early indicator was

An early indicator was  Then came the running battles between

Then came the running battles between  Colleges and universities have traditionally taken two positions on network neutrality. Representing end users, including their campus community and distant students served over the Internet, higher education has taken a strong position in support of the FCC’s network-neutrality proposals, and even urged that they be extended to cover cellular networks. As operators of networks funded and designed to support campuses’ instructional, research, and administrative functions, however, higher education also has taken the position that campus networks, like home, company, and other private networks, should continue to be exempted from network-neutrality provisions.

Colleges and universities have traditionally taken two positions on network neutrality. Representing end users, including their campus community and distant students served over the Internet, higher education has taken a strong position in support of the FCC’s network-neutrality proposals, and even urged that they be extended to cover cellular networks. As operators of networks funded and designed to support campuses’ instructional, research, and administrative functions, however, higher education also has taken the position that campus networks, like home, company, and other private networks, should continue to be exempted from network-neutrality provisions. Why should colleges and universities care about this new network-neutrality battleground? Because in addition to representing end users and operating private networks, campuses are increasingly providing instruction to distant students over the Internet.

Why should colleges and universities care about this new network-neutrality battleground? Because in addition to representing end users and operating private networks, campuses are increasingly providing instruction to distant students over the Internet.  Unlike Netflix, however, individual campuses probably cannot afford to pay for direct connections to all of their students’ last-mile networks, or to place servers in distant data centers. They thus depend on their first-mile networks’ willingness to peer effectively with backbone and last-mile networks. Yet campuses are rarely major customers of their ISPs, and therefore have little leverage to influence ISPs’ backbone and peering choices. Alternatively, campuses can in theory use their existing connections to R&E networks to deliver instruction. But this is only possible if those R&E networks peer directly and capably with key backbone and last-mile providers. R&E networks generally have not done this.

Unlike Netflix, however, individual campuses probably cannot afford to pay for direct connections to all of their students’ last-mile networks, or to place servers in distant data centers. They thus depend on their first-mile networks’ willingness to peer effectively with backbone and last-mile networks. Yet campuses are rarely major customers of their ISPs, and therefore have little leverage to influence ISPs’ backbone and peering choices. Alternatively, campuses can in theory use their existing connections to R&E networks to deliver instruction. But this is only possible if those R&E networks peer directly and capably with key backbone and last-mile providers. R&E networks generally have not done this.