The Rock, and The Hard Place

Looking into the near-term future—say, between now and 2020—we in higher education have to address two big challenges, both involving IT. Neither admits easy progress. But if we don’t address them, we’ll find ourselves caught between a rock and a hard place.

- The first challenge, the rock, is to deliver high-quality, effective e-learning and curriculum at scale. We know how to do part of that, but key pieces are missing, and it’s not clear how will find them.

- The second challenge, the hard place, is to recognize that enterprise cloud services and personal devices will make campus-based IT operations the last rather than the first resort. This means everything about our IT base, from infrastructure through support, will be changing just as we need to rely on it.

“But wait,” I can hear my generation of IT leaders (and maybe the next) say, “aren’t we already meeting those challenges?”

If we compare today’s e-learning and enterprise IT with that of the recent past, those leaders might rightly suggest, immense change is evident:

- Learning management systems, electronic reserves, video jukeboxes, collaboration environments, streamed and recorded video lectures, online tutors—none were common even in 2000, and they’re commonplace today.

- Commercial administrative systems, virtualized servers, corporate-style email, web front ends—ditto.

That’s progress and achievement we all recognize, applaud, and celebrate. But that progress and achievement overcame past challenges. We can’t rest on our laurels.

We’re not yet meeting the two broad future challenges, I believe, because in each case fundamental and hard-to-predict change lies ahead. The progress we’ve made so far, however progressive and effective, won’t steer us between the rock of e-learning and the hard place of enterprise IT.

The fundamental change that lies ahead for e-learning

is the the transition from campus-based to distance education

Back in the 1990s, Cliff Adelman, then at the US Department of Education, did a pioneering study of student “swirl,” that is, students moving through several institutions, perhaps with work intervals along the way,before earning degrees.

Back in the 1990s, Cliff Adelman, then at the US Department of Education, did a pioneering study of student “swirl,” that is, students moving through several institutions, perhaps with work intervals along the way,before earning degrees.

“The proportion of undergraduate students attending more than one institution,” he wrote, “swelled from 40 percent to 54 percent … during the 1970s and 1980s, with even more dramatic increases in the proportion of students attending more than two institutions.” Adelman predicted that “…we will easily surpass a 60 percent multi-institutional attendance rate by the year 2000.”

Moving from campus to campus for classes is one step; taking classes at home is the next. And so distance education, long constrained by the slow pace and awkward pedagogy of correspondence courses, has come into its own. At first it was relegated to “nontraditional” or “experimental” institutions—Empire State College, Western Governors University, UNext/Cardean (a cautionary tale for another day), Kaplan. Then it went mainstream.

At first this didn’t work: fathom.com, for example, a collaboration among several first-tier research universities led by Columbia, found no market for its high-quality online offerings. (Its Executive Director has just written a thoughtful essay on MOOCs, drawing on her fathom.com experience.)

At first this didn’t work: fathom.com, for example, a collaboration among several first-tier research universities led by Columbia, found no market for its high-quality online offerings. (Its Executive Director has just written a thoughtful essay on MOOCs, drawing on her fathom.com experience.)

Today, though, a great many traditional colleges and universities successfully bring instruction and degree programs to distant students. Within the recent past these traditional institutions have expanded into non-degree efforts like OpenCourseWare and to broadcast efforts like the MOOC-based Coursera and edX. In 2008, 3.7% of students took all their coursework through distance education, and 20.4% took at least one class that way.

Learning management systems, electronic reserves, video jukeboxes, collaboration environments, streamed and recorded video lectures, online tutors, the innovations that helped us overcome past challenges—little of that progress was designed for swirling students who do not set foot on campus.

We know how to deliver effective instruction to motivated students at a distance. Among policy issues we have yet to resolve, we don’t yet know how to

- confirm their identity,

- assess their readiness,

- guide their progress,

- measure their achievement,

- standardize course content,

- construct and validate curriculum across diverse campuses, or

- certify degree attainment

in this imminent world. Those aren’t just IT problems, of course. But solving them will almost certainly challenge IT.

The fundamental change that lies ahead for enterprise technologies

is the transition from campus IT to cloud and personal IT

The locus of control over all three principal elements of campus IT—servers and services, networks, and end-user devices and applications—is shifting rapidly from the institution to customers and third parties.

As recently as ten years ago, most campus IT services, everything from administrative systems through messaging and telephone systems to research technologies, were provided by campus entities using campus-based facilities, sometimes centralized and sometimes not. The same was true for the wired and then wireless networks that provided access to services, and for the desktop and laptop computers faculty, students, and staff used.

As recently as ten years ago, most campus IT services, everything from administrative systems through messaging and telephone systems to research technologies, were provided by campus entities using campus-based facilities, sometimes centralized and sometimes not. The same was true for the wired and then wireless networks that provided access to services, and for the desktop and laptop computers faculty, students, and staff used.

Today shared services are migrating rapidly to servers and systems that reside physically and organizationally elsewhere—the “cloud”—and the same is happening for dedicated services such as research computing. It’s also happening for networks, as carrier-provided cellular technologies compete with campus-provided wired and WiFi networking, and for end-user devices, as highly mobile personal tablets and phones supplant desktop and laptop computers.

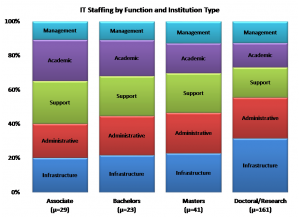

As I wrote in an earlier post about “Enterprise IT,” the scale of enterprise infrastructure and services within IT and the shift in their locus of control have major implications for and the organizations that have provided it. Campus IT organizations grew up around locally-designed services running on campus-owned equipment managed by internal staff. Organization, staffing, and even funding models ensued accordingly. Even in academic computing and user support, “heavy metal” experience was valued highly. The shifting locus of control makes other skills at least as valuable: the ability to negotiate with suppliers, to engage effectively with customers (indeed, to think of them as “customers” rather than “users”), to manage spending and investments under constraint, to explain.

As I wrote in an earlier post about “Enterprise IT,” the scale of enterprise infrastructure and services within IT and the shift in their locus of control have major implications for and the organizations that have provided it. Campus IT organizations grew up around locally-designed services running on campus-owned equipment managed by internal staff. Organization, staffing, and even funding models ensued accordingly. Even in academic computing and user support, “heavy metal” experience was valued highly. The shifting locus of control makes other skills at least as valuable: the ability to negotiate with suppliers, to engage effectively with customers (indeed, to think of them as “customers” rather than “users”), to manage spending and investments under constraint, to explain.

To be sure, IT organizations still require highly skilled technical staff, for example to fine-tune high-performance computing and networking, to ensure that information is kept secure, to integrate systems efficiently, and to identify and authenticate individuals remotely. But these technologies differ greatly from traditional heavy metal, and so must enterprise IT.

The rock, IT, and the hard place

In the long run, it seems to me that the campus IT organization must evolve rapidly to center on seven core activities.

Two of those are substantive:

- making sure that researchers have the technologies they need, and

- making sure that teaching and learning benefit from the best thinking about IT applications and effectiveness.

Four others are more general:

- negotiating and overseeing relationships with outside providers;

- specifying or doing what is necessary for robust integration among outside and internal services;

- striking the right personal/institutional balance between security and privacy for networks, systems, and data; and last but not least

- providing support to customers (both individuals and partner entities).

The seventh core activity, which should diminish over time, is

- operating and supporting legacy systems.

Creative, energetic, competent staff are sine qua non for achieving that kind of forward-looking organization. It’s very hard to do good IT without good, dedicated people, and those are increasingly difficult to find and keep. Not least, this is because colleges and universities compete poorly with the stock options, pay, glitz, and technology the private sector can offer. Therein lies another challenge: promoting loyalty and high morale among staff who know they could be making more elsewhere.

To the extent the rock of e-learning and the hard place of enterprise IT frame our future, we not only need to rethink our organizations and what they do; we also need to rethink how we prepare, promote, and choose leaders for higher-education leaders on campus and elsewhere—the topic, fortuitously, of a recent ECAR report, and of widespread rethinking within EDUCAUSE.

To the extent the rock of e-learning and the hard place of enterprise IT frame our future, we not only need to rethink our organizations and what they do; we also need to rethink how we prepare, promote, and choose leaders for higher-education leaders on campus and elsewhere—the topic, fortuitously, of a recent ECAR report, and of widespread rethinking within EDUCAUSE.

We’ve been through this before, and risen to the challenge.

- Starting around 1980, minicomputers and then personal computers brought IT out of the data center and into every corner of higher education, changing data center, IT organization, and campus in ways we could not even imagine.

- Then in the 1990s campus, regional, and national networks connected everything, with similarly widespread consequences.

We can rise to the challenges again, too, but only if we understand their timing and the transformative implications.