Mythology, Belief, Analytics, & Behavior

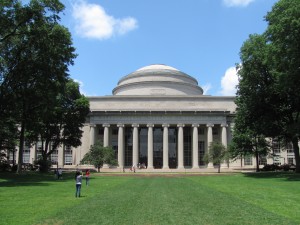

I’m at loose ends after graduating. The Dean for Student Affairs, whom I’ve gotten to know through a year of complicated political and educational advocacy, wants to know more about MIT‘s nascent pass/fail experiment, under which first-year students receive written rather than graded evaluations of their work.

I’m at loose ends after graduating. The Dean for Student Affairs, whom I’ve gotten to know through a year of complicated political and educational advocacy, wants to know more about MIT‘s nascent pass/fail experiment, under which first-year students receive written rather than graded evaluations of their work.

MIT being MIT, “know more” means data: the Dean wants quantitative analysis of patterns in the evaluations. I’m hired to read a semester’s worth, assign each a “Usefulness” score and a “Positiveness” score, and then summarize the results statistically.

Two surprises. First, Usefulness turns out to be much higher than anyone had expected–mostly because evaluations contain lots of “here’s what you can do to improve” advice, rather than lots of terse “you would have gotten a B+” comments, as had been predicted. Second, Positiveness distributes remarkably as grades had for the pre-pass/fail cohort, rather than skewing higher, as had been predicted. Even so, many faculty continue to believe both predictions (that is, they think written evaluations are both generally useless and inappropriately positive).

A byproduct of the assignment is my first exposure to MIT’s glass-house computer facility, an IBM 360 located in the then-new Building 39. In due course I learn that Jay Forrester, an MIT faculty member, had patented the use of 3-D arrays of magnetic cores for computer memory (the read-before-write use of cores, which enabled Forrester’s breakthrough, had been patented by An Wang, another faculty member, of the eponymous calculators and word processors). IBM bought Wang’s patent, but not Forrester’s, and after protracted legal action eventually settled with Forrester in 1964 for $13-million.

A byproduct of the assignment is my first exposure to MIT’s glass-house computer facility, an IBM 360 located in the then-new Building 39. In due course I learn that Jay Forrester, an MIT faculty member, had patented the use of 3-D arrays of magnetic cores for computer memory (the read-before-write use of cores, which enabled Forrester’s breakthrough, had been patented by An Wang, another faculty member, of the eponymous calculators and word processors). IBM bought Wang’s patent, but not Forrester’s, and after protracted legal action eventually settled with Forrester in 1964 for $13-million.

According to MIT mythology, under the Institute’s intellectual-property policy half of the settlement came to the Institute, and that money built Building 39. Only later do I wonder whether the Forrester/IBM/39 mythology is true. But not for long: never let truth stand in the way of a good story.

Not just because mythology often involves memorable, simple stories, belief in mythology is durable. This is important because belief so heavily drives behavior. That belief resists even data-driven contradiction–data analysis rarely yields memorable, simple stories–is one reason analytics so often prove curiously ineffective in modifying institutional behavior.

Two examples, both involving the messy question of copyright infringement by students and what, if anything, campuses should do about it.

44%

I’m having lunch with a very smart, experienced, and impressive senior officer from an entertainment-industry association, whom I’ll call Stan. The only reason universities invest heavily in campus networks, Stan tells me, is to enable students to download and share ever more copyright-infringing movies, TV shows, and music. That’s why campuses remain major distributors of “pirated” entertainment, he says, and therefore why it’s appropriate to subject higher education generally to regulations and sanctions such as the “peer to peer” regulations from the 2008 Higher Education Opportunity Act.

I’m having lunch with a very smart, experienced, and impressive senior officer from an entertainment-industry association, whom I’ll call Stan. The only reason universities invest heavily in campus networks, Stan tells me, is to enable students to download and share ever more copyright-infringing movies, TV shows, and music. That’s why campuses remain major distributors of “pirated” entertainment, he says, and therefore why it’s appropriate to subject higher education generally to regulations and sanctions such as the “peer to peer” regulations from the 2008 Higher Education Opportunity Act.

That Stan believes this results partly from a rhetorical problem with high-performance networks, such as the research networks within and interconnecting colleges and universities. High-performance networks–even those used by broadcasters–usually are engineered to cope with peak loads. Since peaks are occasional, most of the time most network capacity goes unused. If one doesn’t understand this–as Stan doesn’t–then one assumes that the “unused” capacity is in fact being used, but for purposes not being disclosed.

And, as it happens, there’s mythology to fill in the gap: According to a 2005 MPAA study, Stan tells me, higher education accounts for almost half of all copyright infringement. So MPAA, and therefore Stan, knows what campuses aren’t telling us: they’re upgrading campus networks to enable infringement.

But Stan is wrong. There are two big problems with his belief.

First, shortly after MPAA asserted, both publicly and in letters to campus presidents, that 44% of all copyright infringement emanates from college campuses, which is where Stan’s “almost half” comes from, MPAA learned that its data contractor had made a huge arithmetic error. The correct estimate should have been more like 10-15%. But the corrected estimate was never publicized as extensively as the erroneous one: the errors that statisticians make live after them; the corrections are oft interred with their bones.

First, shortly after MPAA asserted, both publicly and in letters to campus presidents, that 44% of all copyright infringement emanates from college campuses, which is where Stan’s “almost half” comes from, MPAA learned that its data contractor had made a huge arithmetic error. The correct estimate should have been more like 10-15%. But the corrected estimate was never publicized as extensively as the erroneous one: the errors that statisticians make live after them; the corrections are oft interred with their bones.

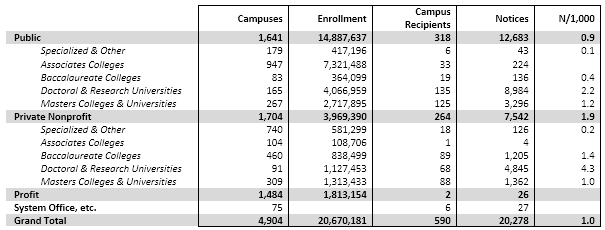

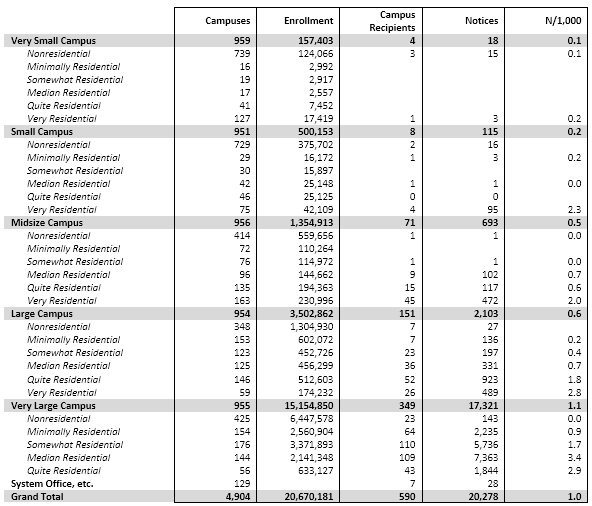

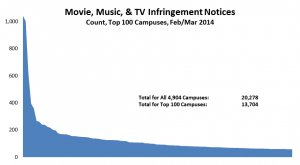

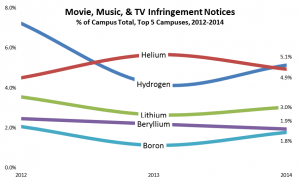

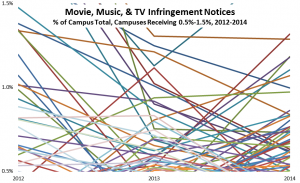

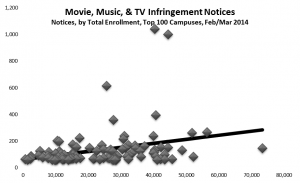

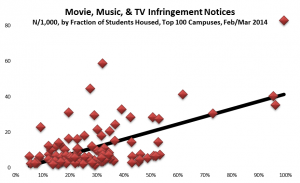

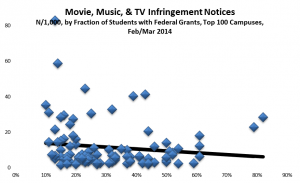

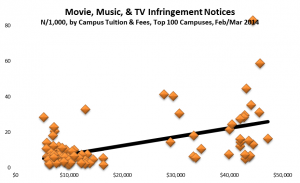

Second, if Stan’s belief is correct, then there should be little difference among campuses in the incidence of copyright infringement, at least among campuses with research-capable networking. Yet this isn’t the case. As I’ve found researching three years of data on the question, the distribution of detected infringement is highly skewed. Most campuses are responsible for little or no distribution of infringing material, presumably because they’re using Packetlogic, Palo Alto firewalls, or similar technologies to manage traffic. Conversely, a few campuses account for the lion’s share of detected infringement.

So there are ample data and analytics contradicting Stan’s belief, and none supporting it. But his belief persists, and colors how he engages the issues.

Targeting

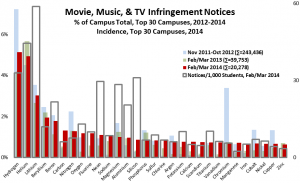

I’m having dinner with the CIO from an eminent research university; I’ll call her Samantha, and her campus Helium (the same name it has in the infringement-data post I cited above). We’re having dinner just as I’m completing my 2013 study, in which Helium has surpassed Hydrogen as the largest campus distributor of copyright-infringing movies, TV shows, and music.

I’m having dinner with the CIO from an eminent research university; I’ll call her Samantha, and her campus Helium (the same name it has in the infringement-data post I cited above). We’re having dinner just as I’m completing my 2013 study, in which Helium has surpassed Hydrogen as the largest campus distributor of copyright-infringing movies, TV shows, and music.

In fact, Helium accounts for 7% of all detected infringement from the 5,000 degree-granting colleges and universities in the United States. I’m thinking that Samantha will want to know this, that she will try to figure out what Helium is doing–or not doing–to stand out as such a sore thumb among peer campuses, and perhaps make some policy or practice changes to bring Helium into closer alignment.

But no: Samantha explains to me that the data are entirely inaccurate. Most of the infringement notices Helium receives are duplicates, she tells me, and in any case the only reason Helium receives so many is that the entertainment industry intentionally targets Helium in its detection and notification processes. Since the data are wrong, she says, there’s no need to change anything at Helium.

I offer to share detailed data with Helium’s network-security staff so that they can look more closely at the issue, but Samantha declines the offer. Nothing changes, and in 2014 Helium is again one of the top recipients of infringement notices (although Hydrogen regains the lead it had held in 2012).

The data Samantha declines to see tell an interesting story, though. The vast majority of Helium’s notices, it turns out, are associated with eight IP addresses. That is, each of those eight IP addresses is cited in hundreds of notices, which may account for Samantha’s comment about “duplicates”. Here’s what’s interesting: the eight addresses are consecutive, and they each account for about the same number of notices. That suggests technology at work, not individuals.

As in Stan’s case, it helps to know something about how campus networks work. Lots of traffic distributed evenly across a small number of IP addresses sounds an awful lot like load balancing, so perhaps those addresses are the front end to some large group of users. “Front end to some large group of users” sounds like an internal network using Network Address Translation (NAT) for its external connections.

As in Stan’s case, it helps to know something about how campus networks work. Lots of traffic distributed evenly across a small number of IP addresses sounds an awful lot like load balancing, so perhaps those addresses are the front end to some large group of users. “Front end to some large group of users” sounds like an internal network using Network Address Translation (NAT) for its external connections.

NAT issues numerous internal IP addresses to users, and then technologically translates those internal addresses traceably into a much smaller set of external addresses. Most campuses use NAT to conserve their limited allocation of external IP addresses, especially for their campus wireless networks. NAT logs, if kept properly, enable campuses to trace connections from insiders to outside and vice versa, and so to resolve those apparent “duplicates”.

So although it’s true that there are lots of duplicate IP addresses among the notices Helium receives, this probably stems from Helium’s use of NAT on its campus wireless. Helium’s data are not incorrect. If Helium were to manage NAT properly, it could figure out where the infringement is coming from, and address it.

Samantha’s belief that copyright holders target specific campuses, like Stan’s that campuses expand networks to encourage infringement, has a source–in this case, a presentation some years back from an industry association to a group of IT staff from a score of research universities. (I attended this session.) Back then, we learned, the association did target campuses, not out of animus, but simply as a data-collection mechanism. The association would choose a campus, look for infringing material being published from the campus’s network, send notices, and then move on to another campus.

Since then, however, the industry had changed its methodology, in large part because the BitTorrent protocol replaced earlier ones as the principal medium for download-based infringement. Because of how BitTorrent works, the industry’s methodology shifted from searching particular networks to searching BitTorrent indexes for particularly popular titles and then seeing which networks were making those titles available.

Since then, however, the industry had changed its methodology, in large part because the BitTorrent protocol replaced earlier ones as the principal medium for download-based infringement. Because of how BitTorrent works, the industry’s methodology shifted from searching particular networks to searching BitTorrent indexes for particularly popular titles and then seeing which networks were making those titles available.

I spent lots of time recently with the industry’s contractors looking closely at that methodology. It appears to treat campus networks equivalently to each other and to commercial networks, and so it’s unlikely that Helium was being targeted as Samantha asserted.

If Samantha had taken the infringement data to her security staff, they probably would have discovered the same thing I did, and either used NAT data to identify offenders, or perhaps to justify policy changes for the wireless network. Same goes for exploring the methodology. But instead Samantha relied on her belief that the data were incorrect and/or targeted

Promoting Analytic Effectiveness

Because of Stan’s and Samantha’s belief in mythology, their organizations’ behavior remains largely uninformed by analytics and data.

A key tenet in decision analysis holds that information has no value (other than the intrinsic value of knowledge) unless the decisions an individual or an institution have before them will turn out differently depending on the information. That is, unless decisions depend on the results of data analysis, it’s not worth collecting or analyzing data.

A key tenet in decision analysis holds that information has no value (other than the intrinsic value of knowledge) unless the decisions an individual or an institution have before them will turn out differently depending on the information. That is, unless decisions depend on the results of data analysis, it’s not worth collecting or analyzing data.

Colleges, universities, and other academic institutions have difficulty accepting this, since the intrinsic value of information is central to their existence. But what’s valuable intrinsically isn’t necessarily valuable operationally.

Generic praise for “data-based decision making” or “analytics” won’t change this. Neither will post-hoc documentation that decisions are consistent with data. Rather, what we need are good, simple stories that will help mythology evolve: case studies of how colleges and universities have successfully and prospectively used data analysis to change their behavior for the better. Simply using data analysis doesn’t suffice, and neither does better behavior: we need stories that vividly connect the two.

Ironically, the best way to combat mythology is with–wait for it–mythology…