Notes on Barter, Privacy, Data, & the Meaning of “Free”

It’s been an interesting few weeks:

- Facebook’s upcoming $100-billion IPO has users wondering why owners get all the money while users provide all the assets.

- Google’s revision of privacy policies has users thinking that something important has changed even though they don’t know what.

- Google has used a loophole in Apple’s browser to gather data about iPhone users.

- Apple has allowed app developers to download users’ address books.

- And over in one of EDUCAUSE’s online discussion groups, the offer of a free book has somehow led security officers to do linguistic analysis of the word “free” as part of a privacy argument.

Lurking under all, I think, are the unheralded and misunderstood resurgence of a sometimes triangular barter economy, confusion about different revenue models, and, yes, disagreement what the word “free” means.

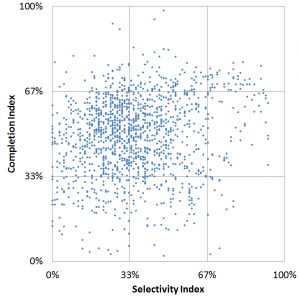

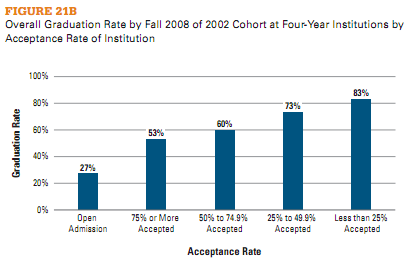

Let’s approach the issue obliquely, starting, in the best academic tradition, with a small-scale research problem. Here’s the hypothetical question, which I might well have asked back when I was a scholar of student choice: Is there a relationship between selectivity and degree completion at 4-year colleges and universities?

As a faculty member in the late 1970s, I’d have gone to the library and used reference tools to locate articles or reports on the subject. If I were unaffiliated and living in Chicago (which I wasn’t back then), I might have gone to the Chicago Public Library, found in its catalog a 2004 report by Laura Horn, and have had that publication pulled from closed-stack storage so I could read it.

By starting with that baseline, of course, I’m merely reminiscing. These days I can obtain the data myself, and do some quick analysis. I know the relevant data are in the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). And those IPEDS data are available online, so I can

By starting with that baseline, of course, I’m merely reminiscing. These days I can obtain the data myself, and do some quick analysis. I know the relevant data are in the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). And those IPEDS data are available online, so I can

(a) download data on 2010 selectivity, undergraduate enrollment, and bachelor’s degrees awarded for the 2,971 US institutions that grant four-year degree and import those data into Excel,

(b) eliminate the 101 system offices and such missing relevant data, the 1,194 that granted fewer than 100 degrees, the 15 institutions reporting suspiciously high degree/enrollment rates, the one that reported no degrees awarded (Miami-Dade College, in case you’re interested), and the 220 that reported no admit rate, and then

(c) for the remaining 1,440 colleges and universities, create a graph of degree completion (somewhat normalized) as a function of selectivity (ditto).

The graph doesn’t tell me much–scatter plots rarely do for large datasets–but a quick regression analysis tells me there’s a modestly positive relationship: 1% higher selectivity (according to my constructed index) translates on average into 1.4% greater completion (ditto). The download, data cleaning, graphing, and analysis take me about 45 minutes all told.

Or I might just use a search engine. When I do that, using “degree completion by selectivity” as the search term, a highly-ranked Google result takes me to an excerpt from a College Board report.

Or I might just use a search engine. When I do that, using “degree completion by selectivity” as the search term, a highly-ranked Google result takes me to an excerpt from a College Board report.

Curiously, that report tells me that “…selectivity is highly correlated with graduation rates,” which is a rather different conclusion than IPEDS gave me. The footnotes help explain this: the College Board includes two-year institutions in its analysis, considers only full-time, first-time students, excludes returning students and transfers, and otherwise chooses its data in ways I didn’t.

The difference between my graph and the College Board’s conclusion is excellent fodder for a discussion of how to evaluate what one finds online — in the quote often (but perhaps mistakenly) attributed to Daniel Patrick Moynihan, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts.” Which gets me thinking about one of the high points in my graduate studies, a Harvard methodology seminar wherein Mike Smith, who was eventually to become US Undersecretary of Education, taught Moynihan what regression analysis is, which in turn reminds me of the closet full of Scotch at the Joint Center for Urban Studies kept full because Moynihan required that no meeting at the Joint go past 4pm without a bottle of Scotch on the table. But I digress.

Since I was logged in with my Google account when I did the search, some of the results might even have been tailored to what Google had learned about me from previous searches. At the very least, the information was tailored to previous searches from the computer I used here in my DC office.

Which brings me to the linguistic dispute among security officers.

A recent EDUCAUSE webinar presenter, during Data Privacy Month, was Matt Ivester, creator of JuicyCampus and author of lol…OMG!: What Every Student Needs to Know About Online Reputation Management, Digital Citizenship and Cyberbullying.

“In honor of Data Privacy Day,” the book’s website announced around the same time, “the full ebook of lol…OMG! (regularly $9.99) is being made available for FREE!” Since Ivester was going to be a guest presenter for EDUCAUSE, we encouraged webinar participants to avail themselves of this offer and to download the book.

One place we did that was in a discussion group we host for IT security professionals. A participant in that discussion group immediately took Ivester to task:

…you can’t download the free book without logging in to Amazon. And, near as I can tell, it’s Kindle- or Kindle-apps-only. In honor of Data Privacy Day. The irony, it drips.

“Pardon the rant,” another participant responded, “but what is the irony here?” Another elaborated:

I intend to download the book but, despite the fact that I can understand why free distribution is being done this way, I still find it ironic that I must disclose information in order to get something that’s being made available at no charge in honor of DPD.

The discussion grew lively, and eventually devolved into a discussion of the word “free”. If one must disclose personal information in order to download a book at no monetary cost, is the book “free”?

The discussion grew lively, and eventually devolved into a discussion of the word “free”. If one must disclose personal information in order to download a book at no monetary cost, is the book “free”?

If words like “free”, “cost”, and “price” refer only to money, the answer is Yes. But money came into existence only to simplify barter economies. In a sense, today’s Internet economy involves a new form of barter that replaces money: If we disclose information about ourselves, then we receive something in return; conversely, vendors offer “free” products in order to obtain information about us.

In a recent post, Ed Bott presented graphs illustrating the different business models behind Microsoft, Apple, and Google. According to Bott, Microsoft is selling software, Apple is selling hardware, and Google is selling advertising.

More to the point here, Microsoft and Apple still focus on traditional binary transactions, confined to themselves and buyers of their products.

Google is different. Google’s triangle trade (which Facebook also follows) offers “free” services to individuals, collects information about those individuals in return, and then uses that information to tailor advertising that it then sells to vendors in return for money. In the triangle, the user of search results pays no money to Google, so in that limited sense it’s “free”. Thus the objection in the Security discussion group: if one directly exchanges something of value for the “free” information, then it’s not free.

Except for my own time, all three answers to my “How does selectivity relate to degree completion?” question were “free”, in the sense I paid no money explicitly for them. All of them cost someone something. But not all no-cost-to-the-user online data is funded through Google-like triangles.

In the case of the Chicago Public Library, my Chicago property taxes plus probably some federal and Illinois grants enabled the library to acquire, catalog, store, and retrieve the Horn report. They also built the spectacular Harold Washington Library where I’d go read it.

In the case of the Chicago Public Library, my Chicago property taxes plus probably some federal and Illinois grants enabled the library to acquire, catalog, store, and retrieve the Horn report. They also built the spectacular Harold Washington Library where I’d go read it.

In the case of IPEDS, my federal tax dollars paid the bill.

In both cases, however, what I paid was unrelated to how much I used the resources, and involved almost no disclosure of my identity or other attributes.

In contrast, the “free” search Google provided involved my giving something of value to Google, namely something about my searches. The same was true for the Ivester fans who downloaded his “free” book from Amazon.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that, as Jerry Seinfeld might say: by allowing Google and Amazon to tailor what they show me based on what they know about me, I get search results or purchase suggestions that are more likely to interest me. That is, not only does Google get value from my disclosure; I also get value from what Google does with that information.

The problem–this is what takes us back to security–is twofold.

- First, an awful lot of users don’t understand how the disclosure-for-focus exchange works, in large part because the other party to the exchange isn’t terribly forthright about it. Sure, I can learn why Google is displaying those particular ads (that’s the “Why these ads?” link in tiny print atop the right column in search results), and if I do that I discover that I can tailor what information Google uses. But unless I make that effort the exchange happens automatically, and each search gets added to what Google will use to customize my future ads.

- Second, and much more problematic, the entities that collect information about us increasingly share what they know. This varies depending whether they’ve learned about us directly through things like credit applications or indirectly through what we search for on the Web, what we purchase from vendors like Amazon, or what we share using social media like Facebook or Twitter. Some companies take pains to assure us they don’t share what they know, but in many cases initial assurances get softened over time (or, as appears to have happened with Apple, are violated through technical or process failures). This is routinely true for Facebook, and many seem to believe it’s what’s behind the recent changes in Google’s privacy policy.

Indeed, companies like Acxiom are in the business of aggregating data about individuals and making them available. Data so collected can help banks combat identity theft by enabling them to test whether credit applicants are who they claim to be. If they fall into the wrong hands, however, the same data can enable subtle forms of redlining or even promote identity theft.

Vendors collecting data about us becomes a privacy issue whose substance depends on whether

- we know what’s going on,

- data are kept and/or shared, and

- we can opt out.

Once we agree to disclose in return for “free” goods, however, the exchange becomes a security issue, because the same data can enable impersonation. It becomes a policy issue because the same data can enable inappropriate or illegal activity.

Once we agree to disclose in return for “free” goods, however, the exchange becomes a security issue, because the same data can enable impersonation. It becomes a policy issue because the same data can enable inappropriate or illegal activity.

The solution to all this isn’t turning back the clock — the new barter economy is here to stay. What we need are transparency, options, and broad-based educational campaigns to help people understand the deal and choose according to their preferences.

As either Stan Delaplane or Calvin Trillin once observed about “market price” listings on restaurant menus (or didn’t — I’m damned if I can find anything authoritative, or for that matter any mention whatsoever of this, but know I read it), “When you learn for the first time that the lobster you just ate cost $50, the only reasonable response is to offer half”.

Unfortunately, in today’s barter economy we pay the price before we get the lobster…

Today, for example, the rapidly growing capability of small smartphones has taxed previously underused cellular networks. Earlier, excess capability in the wired Internet prompted innovation in major services like

Today, for example, the rapidly growing capability of small smartphones has taxed previously underused cellular networks. Earlier, excess capability in the wired Internet prompted innovation in major services like  Progress, convergence, and integration in information technology have driven dramatic and fundamental change in the information technologies faculty, students, colleges, and universities have. That progress is likely to continue.

Progress, convergence, and integration in information technology have driven dramatic and fundamental change in the information technologies faculty, students, colleges, and universities have. That progress is likely to continue. Everyone – or at least everyone between the ages of, say, 12 and 65 – has at least one authenticated online

Everyone – or at least everyone between the ages of, say, 12 and 65 – has at least one authenticated online  It’s striking how many of these assumptions were invalid even as recently as five years ago. Most of the assumptions were invalid a decade before that (and it’s sobering to remember that the “3M” workstation was a lofty goal as recently as 1980 and cost nearly $10,000 in the mid-1980s, yet today’s

It’s striking how many of these assumptions were invalid even as recently as five years ago. Most of the assumptions were invalid a decade before that (and it’s sobering to remember that the “3M” workstation was a lofty goal as recently as 1980 and cost nearly $10,000 in the mid-1980s, yet today’s  In colleges and universities, as in other organizations, information technology can promote progress by enabling administrative processes to become more efficient and by creating diverse, flexible pathways for communication and collaboration within and across different entities. That’s organizational technology, and although it’s very important, it affects higher education much the way it affects other organizations of comparable size.

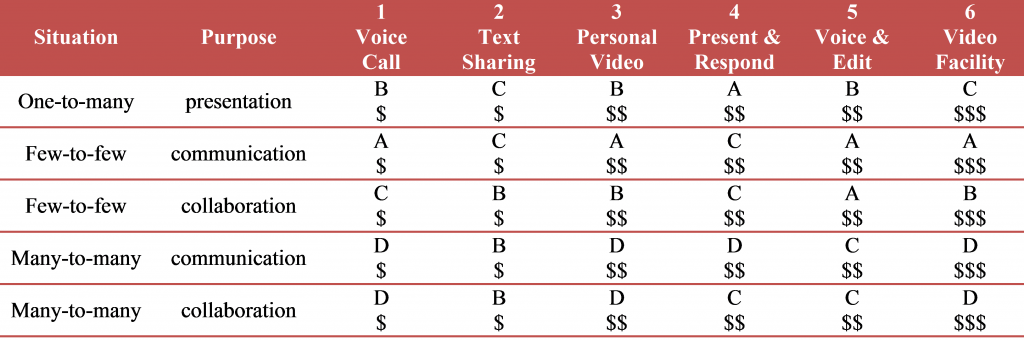

In colleges and universities, as in other organizations, information technology can promote progress by enabling administrative processes to become more efficient and by creating diverse, flexible pathways for communication and collaboration within and across different entities. That’s organizational technology, and although it’s very important, it affects higher education much the way it affects other organizations of comparable size. For example, by storing and distributing materials electronically, by enabling lectures and other events to be streamed or recorded, and by providing a medium for one-to-one or collective interactions among faculty and students, IT potentially expedites and extends traditional roles and transactions. Similarly, search engines and network-accessible library and reference materials vastly increase faculty and students access. The effect, although profound, nevertheless falls short of transformational. Chairs outside faculty doors give way to “learning management systems” like

For example, by storing and distributing materials electronically, by enabling lectures and other events to be streamed or recorded, and by providing a medium for one-to-one or collective interactions among faculty and students, IT potentially expedites and extends traditional roles and transactions. Similarly, search engines and network-accessible library and reference materials vastly increase faculty and students access. The effect, although profound, nevertheless falls short of transformational. Chairs outside faculty doors give way to “learning management systems” like  For example, the

For example, the  This most productively involves experience that otherwise might have been unaffordable, dangerous, or otherwise infeasible. Simulated chemistry laboratories and factories were an early example – students could learn to

This most productively involves experience that otherwise might have been unaffordable, dangerous, or otherwise infeasible. Simulated chemistry laboratories and factories were an early example – students could learn to  This is the most controversial application of learning technology – “Why do we need faculty to teach calculus on thousands of different campuses, when it can be taught online by a computer?” – but also one that drives most discussion of how technology might transform higher education. It has emerged especially for disciplines and topics where instructors convey what they know to students through classroom lectures, readings, and tutorials. PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automated Teaching Operations) emerged from the

This is the most controversial application of learning technology – “Why do we need faculty to teach calculus on thousands of different campuses, when it can be taught online by a computer?” – but also one that drives most discussion of how technology might transform higher education. It has emerged especially for disciplines and topics where instructors convey what they know to students through classroom lectures, readings, and tutorials. PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automated Teaching Operations) emerged from the  Sometimes a student gets all four together. For example, MIT marked me even before I enrolled as someone likely to play a role in technology (admission), taught me a great deal about science and engineering generally, electrical engineering in particular, and their social and economic context (instruction), documented through grades based on exams, lab work, and classroom participation that I had mastered (or failed to master) what I’d been taught (certification), and immersed me in an environment wherein data-based argument and rhetoric guided and advanced organizational life, and thereby helped me understand how to work effectively within organizations, groups, and society (socialization).

Sometimes a student gets all four together. For example, MIT marked me even before I enrolled as someone likely to play a role in technology (admission), taught me a great deal about science and engineering generally, electrical engineering in particular, and their social and economic context (instruction), documented through grades based on exams, lab work, and classroom participation that I had mastered (or failed to master) what I’d been taught (certification), and immersed me in an environment wherein data-based argument and rhetoric guided and advanced organizational life, and thereby helped me understand how to work effectively within organizations, groups, and society (socialization). Instruction is an especially fertile domain for technological progress. This is because three trends converge around it:

Instruction is an especially fertile domain for technological progress. This is because three trends converge around it: One problem with such a future is that socialization, a key function of higher education, gets lost. This points the way to one major technology challenge for the future: Developing online mechanisms, for students who are scattered across the nation or the world, that provide something akin to rich classroom and campus interaction. Such interaction is central to the success of, for example, elite liberal-arts colleges and major residential universities. Many advocates of distance education believe that social media such as Facebook groups can provide this socialization, but that potential has yet to be realized.

One problem with such a future is that socialization, a key function of higher education, gets lost. This points the way to one major technology challenge for the future: Developing online mechanisms, for students who are scattered across the nation or the world, that provide something akin to rich classroom and campus interaction. Such interaction is central to the success of, for example, elite liberal-arts colleges and major residential universities. Many advocates of distance education believe that social media such as Facebook groups can provide this socialization, but that potential has yet to be realized. Drivers headed for

Drivers headed for

“There are two possible solutions,” Hercule Poirot says to the assembled suspects in Murder on the Orient Express (that’s p. 304 in

“There are two possible solutions,” Hercule Poirot says to the assembled suspects in Murder on the Orient Express (that’s p. 304 in  The straightforward projection, analogous to Poirot’s simpler solution (an unknown stranger committed the crime, and escaped undetected), stems from projections how institutions themselves might address each of the IT domains as new services and devices become available, especially cloud-based services and consumer-based end-user devices. The core assumptions are that the important loci of decisions are intra-institutional, and that institutions make their own choices to maximize local benefit (or, in the economic terms I mentioned in

The straightforward projection, analogous to Poirot’s simpler solution (an unknown stranger committed the crime, and escaped undetected), stems from projections how institutions themselves might address each of the IT domains as new services and devices become available, especially cloud-based services and consumer-based end-user devices. The core assumptions are that the important loci of decisions are intra-institutional, and that institutions make their own choices to maximize local benefit (or, in the economic terms I mentioned in  One clear consequence of such straightforward evolution is a continuing need for central guidance and management across essentially the current array of IT domains. As I tried to suggest in

One clear consequence of such straightforward evolution is a continuing need for central guidance and management across essentially the current array of IT domains. As I tried to suggest in  If we think about the future unconventionally (as Poirot does in his second solution — spoiler in the last section below!), a somewhat more radical, extra-institutional projection emerges. What if Accenture, McKinsey, and Bain are right, and IT contributes very little to the distinctiveness of institutions — in which case colleges and universities have no business doing IT idiosyncratically or even individually?

If we think about the future unconventionally (as Poirot does in his second solution — spoiler in the last section below!), a somewhat more radical, extra-institutional projection emerges. What if Accenture, McKinsey, and Bain are right, and IT contributes very little to the distinctiveness of institutions — in which case colleges and universities have no business doing IT idiosyncratically or even individually? Despite changes in technology and economics, and some organizational evolution, higher education remains largely hierarchical. Vertically-organized colleges and universities grant degrees based on curricula largely determined internally, curricula largely comprise courses offered by the institution, institutions hire their own faculty to teach their own courses, and students enroll as degree candidates in a particular institution to take the courses that institution offers and thereby earn degrees. As

Despite changes in technology and economics, and some organizational evolution, higher education remains largely hierarchical. Vertically-organized colleges and universities grant degrees based on curricula largely determined internally, curricula largely comprise courses offered by the institution, institutions hire their own faculty to teach their own courses, and students enroll as degree candidates in a particular institution to take the courses that institution offers and thereby earn degrees. As  The first challenge, which is already being widely addressed in colleges, universities, and other entities, is distance education: how to deliver instruction and promote learning effectively at a distance. Some efforts to address this challenge involve extrapolating from current models (many community colleges, “laptop colleges”, and for-profit institutions are examples of this), some involve recycling existing materials (Open CourseWare, and to a large extent the Khan Academy), and some involve experimenting with radically different approaches such as game-based simulation. There has already been considerable success with effective distance education, and more seems likely in the near future.

The first challenge, which is already being widely addressed in colleges, universities, and other entities, is distance education: how to deliver instruction and promote learning effectively at a distance. Some efforts to address this challenge involve extrapolating from current models (many community colleges, “laptop colleges”, and for-profit institutions are examples of this), some involve recycling existing materials (Open CourseWare, and to a large extent the Khan Academy), and some involve experimenting with radically different approaches such as game-based simulation. There has already been considerable success with effective distance education, and more seems likely in the near future. As courses relate to curricula without depending on a particular institution, it becomes possible to imagine divorcing the offering of courses from the awarding of degrees. In this radical, no-longer-vertical future, some institutions might simply sell instruction and other learning resources, while others might concentrate on admitting students to candidacy, vetting their choices of and progress through coursework offered by other institutions, and awarding degrees. (Of course, some might try to continue both instructing and certifying.) To manage all this, it will clearly be necessary to gather, hold, and appraise student records in some shared or central fashion.

As courses relate to curricula without depending on a particular institution, it becomes possible to imagine divorcing the offering of courses from the awarding of degrees. In this radical, no-longer-vertical future, some institutions might simply sell instruction and other learning resources, while others might concentrate on admitting students to candidacy, vetting their choices of and progress through coursework offered by other institutions, and awarding degrees. (Of course, some might try to continue both instructing and certifying.) To manage all this, it will clearly be necessary to gather, hold, and appraise student records in some shared or central fashion. Poirot’s second solution to the Ratchett murder (everyone including the butler did it) requires astonishing and improbable synchronicity among a large number of widely dispersed individuals. That’s fine for a mystery novel, but rarely works out in real life.

Poirot’s second solution to the Ratchett murder (everyone including the butler did it) requires astonishing and improbable synchronicity among a large number of widely dispersed individuals. That’s fine for a mystery novel, but rarely works out in real life. Back in 1977,

Back in 1977,  Higher education traditionally has placed a high value on institutional individuality. Some years back a Harvard faculty colleague of mine,

Higher education traditionally has placed a high value on institutional individuality. Some years back a Harvard faculty colleague of mine,  At the same time, it has failed to make the critical distinction between what

At the same time, it has failed to make the critical distinction between what  The dilemma is this:

The dilemma is this: And so the $64 question: What would break this cycle? The answer is simple: sharing information, and committing to joint action. If the prisoners could communicate before deciding whether to defect or cooperate, their rational choice would be to cooperate. If colleges shared information about their plans and their deals, the likelihood of effective joint action would increase sharply. That would be good for the colleges and not so good for the vendor. From this perspective, it’s clear why non-disclosure clauses are so common in vendor contracts.

And so the $64 question: What would break this cycle? The answer is simple: sharing information, and committing to joint action. If the prisoners could communicate before deciding whether to defect or cooperate, their rational choice would be to cooperate. If colleges shared information about their plans and their deals, the likelihood of effective joint action would increase sharply. That would be good for the colleges and not so good for the vendor. From this perspective, it’s clear why non-disclosure clauses are so common in vendor contracts.