IT and Post-Institutional Higher Education: Will We Still Need Brad When He’s 54?

“There are two possible solutions,” Hercule Poirot says to the assembled suspects in Murder on the Orient Express (that’s p. 304 in the Kindle edition, but the 1974 movie starring Albert Finney is way better than the book, and it and the book are both much better than the abominable 2011 PBS version with David Suchet). “I shall put them both before you,” Poirot continues, “…to judge which solution is the right one.”

“There are two possible solutions,” Hercule Poirot says to the assembled suspects in Murder on the Orient Express (that’s p. 304 in the Kindle edition, but the 1974 movie starring Albert Finney is way better than the book, and it and the book are both much better than the abominable 2011 PBS version with David Suchet). “I shall put them both before you,” Poirot continues, “…to judge which solution is the right one.”

So it is for the future role, organization, and leadership of higher-education IT. There are two possible solutions. There’s a reasonably straightforward projection how the role of IT in higher education will evolve into the mid-range future, but there’s also a more complicated one. The first assumes institutional continuity and evolutionary change. The second doesn’t.

IT Domains

How does IT serve higher education? Let me count the ways:

- Infrastructure for the transfer and storage of pedagogical, bibliographic, research, operational, and administrative information, in close synergy with other physical infrastructure such as plumbing, wiring, buildings, sensors, controls, roads, and vehicles. This includes not only hardware such as processors, storage, networking, and end-user devices, but also basic functionality such as database management and hosting (or virtualizing) servers.

- Administrative systems that manage, analyze, and display the information students, faculty, and staff need to manage their own work and that of their departments. This includes identity management, authentication, and other so-called “middleware” through which institutions define their communities.

- Pedagogical applications students and faculty need to enable teaching and learning, including tools for data analysis, bibliography, simulation, writing, multimedia, presentations, discussion, and guidance.

- Research tools faculty and students need to advance knowledge, including some tools that also serve pedagogy plus a broad array of devices and systems to measure, gather, simulate, manage, share, distill, analyze, display, and otherwise bring data to bear on scholarly questions.

- Community services to support interaction and collaboration, including systems for messaging, collaboration, broadcasting, and socialization both within campuses and across their boundaries.

“…A Suit of Wagon Lit Uniform…and a Pass Key…”

The straightforward projection, analogous to Poirot’s simpler solution (an unknown stranger committed the crime, and escaped undetected), stems from projections how institutions themselves might address each of the IT domains as new services and devices become available, especially cloud-based services and consumer-based end-user devices. The core assumptions are that the important loci of decisions are intra-institutional, and that institutions make their own choices to maximize local benefit (or, in the economic terms I mentioned in an earlier post, to maximize their individual utility.)

The straightforward projection, analogous to Poirot’s simpler solution (an unknown stranger committed the crime, and escaped undetected), stems from projections how institutions themselves might address each of the IT domains as new services and devices become available, especially cloud-based services and consumer-based end-user devices. The core assumptions are that the important loci of decisions are intra-institutional, and that institutions make their own choices to maximize local benefit (or, in the economic terms I mentioned in an earlier post, to maximize their individual utility.)

Most current thinking in this vein goes something like this:

- We will outsource generic services, platforms, and storage, and perhaps

- consolidate and standardize support for core applications and

- leave users on their own insofar as commercial devices such as phones and tablets are concerned, but

- we must for the foreseeable future continue to have administrative systems securely dedicated and configured for our unique institutional needs, and similarly

- we must maintain control over our pedagogical applications and research tools since they help distinguish us from the competition.

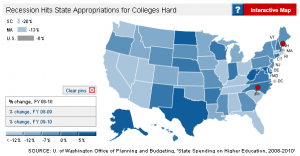

Evolution based on this thinking entails dramatic shrinkage in data-center facilities, as virtualized servers housed in or provided by commercial or collective entities replace campus-based hosting of major systems. It entails several key administrative and community-service systems being replaced by standard commercial offerings — for example, the replacement of expense-reimbursement systems by commercial products such as Concur, of dedicated payroll systems by commercial services such as ADP, and of campus messaging, calendaring, and even document-management systems by more general services such as Google’s or Microsoft’s. Finally, thinking like this typically drives consolidation and standardization of user support, bringing departmental support entities into alignment if not under the authority of central IT, and standardizing requirements and services to reduce response times and staff costs.

How might higher-education IT evolve if this is how things go? In particular, what effects would it have on IT organization, and leadership?

One clear consequence of such straightforward evolution is a continuing need for central guidance and management across essentially the current array of IT domains. As I tried to suggest in a recent article, the nature of that guidance and management would change, in that control would give way to collaboration and influence. But institutions would retain responsibility for IT functions, and it would remain important for important systems to be managed or procured centrally for the general good. Although the skills required of the “chief information officer” would be different, CIOs would still be necessary, and most cross-institutional efforts would be mediated through them. Many of those cross-institutional efforts would involve coordinated action of various kinds, ranging from similar approaches to vendors through collective procurement to joint development.

One clear consequence of such straightforward evolution is a continuing need for central guidance and management across essentially the current array of IT domains. As I tried to suggest in a recent article, the nature of that guidance and management would change, in that control would give way to collaboration and influence. But institutions would retain responsibility for IT functions, and it would remain important for important systems to be managed or procured centrally for the general good. Although the skills required of the “chief information officer” would be different, CIOs would still be necessary, and most cross-institutional efforts would be mediated through them. Many of those cross-institutional efforts would involve coordinated action of various kinds, ranging from similar approaches to vendors through collective procurement to joint development.

We’d still need Brads.

“Say What You Like, Trial by Jury is a Sound System…”

If we think about the future unconventionally (as Poirot does in his second solution — spoiler in the last section below!), a somewhat more radical, extra-institutional projection emerges. What if Accenture, McKinsey, and Bain are right, and IT contributes very little to the distinctiveness of institutions — in which case colleges and universities have no business doing IT idiosyncratically or even individually?

If we think about the future unconventionally (as Poirot does in his second solution — spoiler in the last section below!), a somewhat more radical, extra-institutional projection emerges. What if Accenture, McKinsey, and Bain are right, and IT contributes very little to the distinctiveness of institutions — in which case colleges and universities have no business doing IT idiosyncratically or even individually?

In that case,

- we will outsource almost all IT infrastructure, applications, services, and support, either to collective enterprises or to commercial providers, and therefore

- we will not need data centers or staff, including server administrators, programmers, and administrative-systems technical staff, so that

- the role of institutional IT will be largely to provide only highly tailored support for research and instruction, which means that

- in most cases means there will be little to be gained from centralizing IT,

- it will make sense for academic departments to do their own IT, and

- we can rely on individual business units to negotiate appropriate administrative systems and services, and so

- the balance will shift from centralized to decentralized IT organization and staffing.

What if we’re right that mobility, broadband, cloud services, and distance learning are maturing to the point where they can transform education, so that we have simultaneous and similarly radical change on the academic front?

Despite changes in technology and economics, and some organizational evolution, higher education remains largely hierarchical. Vertically-organized colleges and universities grant degrees based on curricula largely determined internally, curricula largely comprise courses offered by the institution, institutions hire their own faculty to teach their own courses, and students enroll as degree candidates in a particular institution to take the courses that institution offers and thereby earn degrees. As Jim March used to point out, higher education today (well, okay, twenty years ago, when I worked with him at Stanford) is pretty similar to its origins: groups sitting around on rocks talking about books they’ve read.

Despite changes in technology and economics, and some organizational evolution, higher education remains largely hierarchical. Vertically-organized colleges and universities grant degrees based on curricula largely determined internally, curricula largely comprise courses offered by the institution, institutions hire their own faculty to teach their own courses, and students enroll as degree candidates in a particular institution to take the courses that institution offers and thereby earn degrees. As Jim March used to point out, higher education today (well, okay, twenty years ago, when I worked with him at Stanford) is pretty similar to its origins: groups sitting around on rocks talking about books they’ve read.

It’s never been that simple, of course. Most students take some of their coursework from other institutions, some transfer from one to another, and since the 1960s there have been examples of network-based teaching. But the model has been remarkably robust across time and borders. It depends critically on the metaphor of the “campus”, the idea that students will be in one place for their studies.

Mobility, broadband, and the cloud redefine “campus” in ways that call the entire model into question, and thereby may transform higher education. A series of challenges lies ahead on this path. If we tackle and overcome these challenges, higher education, perhaps even including its role in research, could change in very fundamental ways.

The first challenge, which is already being widely addressed in colleges, universities, and other entities, is distance education: how to deliver instruction and promote learning effectively at a distance. Some efforts to address this challenge involve extrapolating from current models (many community colleges, “laptop colleges”, and for-profit institutions are examples of this), some involve recycling existing materials (Open CourseWare, and to a large extent the Khan Academy), and some involve experimenting with radically different approaches such as game-based simulation. There has already been considerable success with effective distance education, and more seems likely in the near future.

The first challenge, which is already being widely addressed in colleges, universities, and other entities, is distance education: how to deliver instruction and promote learning effectively at a distance. Some efforts to address this challenge involve extrapolating from current models (many community colleges, “laptop colleges”, and for-profit institutions are examples of this), some involve recycling existing materials (Open CourseWare, and to a large extent the Khan Academy), and some involve experimenting with radically different approaches such as game-based simulation. There has already been considerable success with effective distance education, and more seems likely in the near future.

As it becomes feasible to teach and learn at a distance, so that students can be “located” on several “campuses” at once, students will have no reason to take all their coursework from a single institution. A question arises: If coursework comes from different “campuses”, who defines curriculum? Standardizing curriculum, as is already done in some professional graduate programs, is one way to achieve address this problem — that is, we may define curriculum extra-institutionally, “above the campus”. Such standardization requires cross-institutional collaboration, oversight from professional associations or guilds, and/or government regulation. None of this works very well today, in part because such standardization threatens institutional autonomy and distinctiveness. But effective distance teaching and learning may impel change.

As courses relate to curricula without depending on a particular institution, it becomes possible to imagine divorcing the offering of courses from the awarding of degrees. In this radical, no-longer-vertical future, some institutions might simply sell instruction and other learning resources, while others might concentrate on admitting students to candidacy, vetting their choices of and progress through coursework offered by other institutions, and awarding degrees. (Of course, some might try to continue both instructing and certifying.) To manage all this, it will clearly be necessary to gather, hold, and appraise student records in some shared or central fashion.

As courses relate to curricula without depending on a particular institution, it becomes possible to imagine divorcing the offering of courses from the awarding of degrees. In this radical, no-longer-vertical future, some institutions might simply sell instruction and other learning resources, while others might concentrate on admitting students to candidacy, vetting their choices of and progress through coursework offered by other institutions, and awarding degrees. (Of course, some might try to continue both instructing and certifying.) To manage all this, it will clearly be necessary to gather, hold, and appraise student records in some shared or central fashion.

To the extent this projection is valid, not only does the role of IT within institutions change, but the very role of institutions in higher education changes. It remains important that local support be available to support the IT components of distinctive coursework, and of course to support research, but almost everything else — administrative and community services, infrastructure, general support — becomes either so standardized and/or outsourced as to require no institutional support, or becomes an activity for higher education generally rather than colleges or universities individually. In the extreme case, the typical institution really doesn’t need a central IT organization.

In this scenario, individual colleges and universities don’t need Brads.

“…What Should We Tell the Yugo-Slavian Police?”

Poirot’s second solution to the Ratchett murder (everyone including the butler did it) requires astonishing and improbable synchronicity among a large number of widely dispersed individuals. That’s fine for a mystery novel, but rarely works out in real life.

Poirot’s second solution to the Ratchett murder (everyone including the butler did it) requires astonishing and improbable synchronicity among a large number of widely dispersed individuals. That’s fine for a mystery novel, but rarely works out in real life.

I therefore don’t suggest that the radical scenario I sketched above will come to pass. As many scholars of higher education have pointed out, colleges and universities are organized and designed to resist change. So long as society entrusts higher education to colleges and universities and other entities like them, we are likely to see evolutionary rather than radical change. So my extreme scenario, perhaps absurd on its face, seeks to only to suggest that we would do well to think well beyond institutional boundaries as we promote IT in higher education and consider its transformative potential.

And more: if we’re serious about the potentially transformative role of mobility, broadband, and the cloud in higher education, we need to consider not only what IT might change but also what effects that change will have on IT itself — and especially on its role within colleges and universities and across higher education.

Back in 1977,

Back in 1977,  Higher education traditionally has placed a high value on institutional individuality. Some years back a Harvard faculty colleague of mine,

Higher education traditionally has placed a high value on institutional individuality. Some years back a Harvard faculty colleague of mine,  At the same time, it has failed to make the critical distinction between what

At the same time, it has failed to make the critical distinction between what  The dilemma is this:

The dilemma is this: And so the $64 question: What would break this cycle? The answer is simple: sharing information, and committing to joint action. If the prisoners could communicate before deciding whether to defect or cooperate, their rational choice would be to cooperate. If colleges shared information about their plans and their deals, the likelihood of effective joint action would increase sharply. That would be good for the colleges and not so good for the vendor. From this perspective, it’s clear why non-disclosure clauses are so common in vendor contracts.

And so the $64 question: What would break this cycle? The answer is simple: sharing information, and committing to joint action. If the prisoners could communicate before deciding whether to defect or cooperate, their rational choice would be to cooperate. If colleges shared information about their plans and their deals, the likelihood of effective joint action would increase sharply. That would be good for the colleges and not so good for the vendor. From this perspective, it’s clear why non-disclosure clauses are so common in vendor contracts.