The Ghost is Ready, but the Meat is Raw

Old joke. Someone writes a computer program (creates an app?) that translates from English into Russian (say) and vice versa. Works fine on simple stuff, so the next test is a a bit harder: “the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.” The program/app translates the phrase into Russian, then the tester takes the result, feeds it back into the program/app, and translates it back into English. Result: “The ghost is ready, but the meat is raw.”

Old joke. Someone writes a computer program (creates an app?) that translates from English into Russian (say) and vice versa. Works fine on simple stuff, so the next test is a a bit harder: “the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.” The program/app translates the phrase into Russian, then the tester takes the result, feeds it back into the program/app, and translates it back into English. Result: “The ghost is ready, but the meat is raw.”

(The starting phrase is from Matthew 26:41 — the King James version has “indeed” before “willing”, ASV doesn’t, and weirdly enough, if you try this in Google Translate, the joke falls flat, because you get an accurate translation to Russian and back, except for some reason you end up with an extra “indeed” in the final version. It’s almost as though Google Translate has figured out where the quotation came from, and then substituted the King James version for the ASV one, but not quite correctly. Spooky. But I digress.)

Old joke, yes. Tired, even. But, as usual, it’s a metaphor, in this case for a problem that will only become larger as higher education outsources or contracts for ever more of its activity: we think we’ve doing the right thing when we contract with outside providers, but the actual effect of the contract, once it takes effect, isn’t quite what we expected. If we’re lucky, we figure this out before we’re irrevocably committed. If we’re unlucky, we box ourselves in.

Two examples.

1. Microsoft Site Licensing

About a decade ago, several of us were at an Internet2 meeting. A senior Microsoft manager spoke about relations with higher education (although looking back, I can’t see why Microsoft would present at I2. Maybe it wasn’t an I2 meeting, but let’s just say it was — never let truth get in the way of a good story). At the time, instead of buying a copy of Office for each computer, as Microsoft licenses required, many students, staff, and faculty simply installed Microsoft Office on multiple machines from one purchased copy — or even copied the installation disks and passed them around. That may save money, but it’s copyright infringement, and illegal.

About a decade ago, several of us were at an Internet2 meeting. A senior Microsoft manager spoke about relations with higher education (although looking back, I can’t see why Microsoft would present at I2. Maybe it wasn’t an I2 meeting, but let’s just say it was — never let truth get in the way of a good story). At the time, instead of buying a copy of Office for each computer, as Microsoft licenses required, many students, staff, and faculty simply installed Microsoft Office on multiple machines from one purchased copy — or even copied the installation disks and passed them around. That may save money, but it’s copyright infringement, and illegal.

Microsoft’s response to this problem had been threefold:

- it began incorporating copy protection and other digital-rights-management (DRM) mechanisms into its installation media so that they couldn’t be copied,

- it began berating campuses for tolerating the illegal copying (and in some cases attempted to audit compliance with licenses by searching campus computers for illegally obtained software), and

- it sought to centralize campus procurement of Microsoft software by tailoring and refining its so-called “Select” volume-discount program to encourage campuses to license software campus-wide.

Problem was, the “Select” agreement required campuses to count how many copies of software they licensed, and to maintain records that would enable Microsoft to determine whether each installed copy on campus was properly licensed. This entailed elaborate bookkeeping and tracking mechanisms, exposed campuses to audit risk, and its costs into the future were unpredictable. The volume-discount “Select” program was clearly a step forward, but it fell far short of actually appealing to campuses.

So the several of us in the Internet2 session (or wherever it was) took the Microsoft manager aside afterwards, told him Microsoft needed a more attractive licensing model for campuses, and suggested what that might be.

To our surprise, Microsoft followed up, and the rump-group discussions evolved into the initial version of the Microsoft Campus Agreement. The Campus Agreement (since replaced by Enrollment for Education Solutions, EES) was a true site license: glossing over some complexities and details, its general terms were that campuses would pay Microsoft based on their size and the number of different products they wished to license, and in return would be permitted to use as many copies of those products as they liked.

Most important from the campus perspective, the Campus Agreement included no requirement to track or count individual copies of the licensed products, thereby making all copies legal; in fact, campuses could make their own copies of installation media. Most important from the Microsoft perspective, Campus Agreement pricing was set so that the typical campus would still pay Microsoft about as much as Microsoft had been receiving from that campus’s central or departmental users for Select or individual copies; that is, Micorsoft’s revenue from campuses would not decline.

Most important from the campus perspective, the Campus Agreement included no requirement to track or count individual copies of the licensed products, thereby making all copies legal; in fact, campuses could make their own copies of installation media. Most important from the Microsoft perspective, Campus Agreement pricing was set so that the typical campus would still pay Microsoft about as much as Microsoft had been receiving from that campus’s central or departmental users for Select or individual copies; that is, Micorsoft’s revenue from campuses would not decline.

The Campus Agreement did entail a fundamental change that was less appealing. In effect, campuses were paying to rent software, with Microsoft agreeing to provide updates at no additional cost, rather than campuses buying copies and then periodically paying to update them. Although it included a few other lines, for the most part the Campus Agreement covered Microsoft’s operating-system and Office products.

Win-win, right? Lots of campuses signed up for the Campus Agreement. It largely eliminated talk about “piracy” of MS-Office products in higher education (enhanced DRM played an important role in this too), and it stabilized costs for most Microsoft client software. It was very popular with students, faculty, and staff, especially since the Campus Agreement allowed institutionally-provided software to be installed on home computers.

But at least one campus, which I’ll call Pi University, balked. The Campus Agreement, PiU’s golf-loving CIO pointed out, had a provision no one had read carefully: if PiU withdrew from the Campus Agreement, he said, it might be required to list and pay for all the software copies that PiU or its students, faculty, and staff had acquired under the Campus Agreement — that is, to buy what it had been renting. The PiU CIO said that he had no way to comply with such a provision, and that therefore PiU could not in good faith sign an agreement that included it.

But at least one campus, which I’ll call Pi University, balked. The Campus Agreement, PiU’s golf-loving CIO pointed out, had a provision no one had read carefully: if PiU withdrew from the Campus Agreement, he said, it might be required to list and pay for all the software copies that PiU or its students, faculty, and staff had acquired under the Campus Agreement — that is, to buy what it had been renting. The PiU CIO said that he had no way to comply with such a provision, and that therefore PiU could not in good faith sign an agreement that included it.

Some of us thought the PiU CIO’s point was valid but inconsequential. First, some of us didn’t believe that Microsoft would ever enforce the buy-what-you’d-rented clause, so that it presented little actual risk. Second, some of us pointed out that since there was no requirement that campuses document how many copies they distributed, and in general the distribution would be independent of Microsoft, a campus leaving the Campus Agreement could simply cite any arbitrary number of copies as the basis for its exit payment. Therefore, even if Microsoft enforced the clause, estimating the associated payment was entirely under the campus’s control. Those of who believed these arguments went forward with the Campus Agreement; Pi University didn’t.

So the ghost was ready (higher education had gotten most of what it wanted), but the meat was raw (what we wanted turned out problematic in ways no one had really thought through).

Now let’s turn to a more current case.

2. Outsourcing Campus Bookstores

In February 2012 EDUCAUSE agreed to work with Internet2 on an electronic textbooks pilot. This was to be the third in a series of pilots: Indiana University had undertaken one for the fall of 2011, it and a few other campuses had worked with Internet2 on second proof-of-concept pilot for the spring of 2012, and the third pilot was to include a broader array of institutions.

In February 2012 EDUCAUSE agreed to work with Internet2 on an electronic textbooks pilot. This was to be the third in a series of pilots: Indiana University had undertaken one for the fall of 2011, it and a few other campuses had worked with Internet2 on second proof-of-concept pilot for the spring of 2012, and the third pilot was to include a broader array of institutions.

Driving these efforts were the observations that textbook prices figured prominently in spiraling out-of-pocket college-attendance costs, that electronic textbooks might help attenuate those prices, and that electronic textbooks also might enable campuses to move from individual student purchases to more efficient site licenses, perhaps bypassing unnecessary intermediaries.

A small team planned the pilot, and began soliciting participation in mid-March. By April 7, the initial deadline, 70 institutions had expressed interest. Over 100 people joined an informational webinar two days later, and it looks as though about 25 institutions will manage to participate and help higher education, publishers, and e-reader providers understand their joint future better.

The ghost/meat example here isn’t the etext pilot itself. Rather, it’s something that caused many interested institutions to withdraw from the pilot: campus bookstore outsourcing.

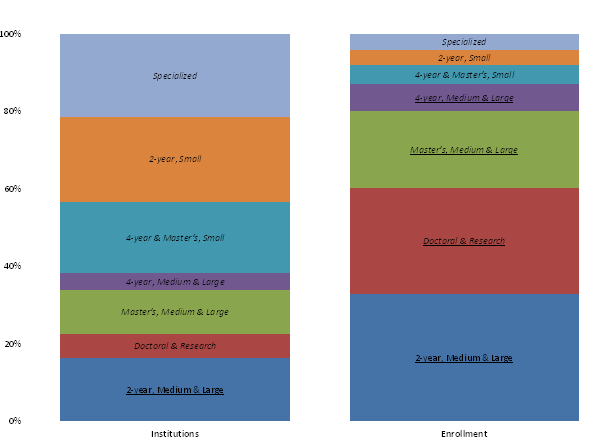

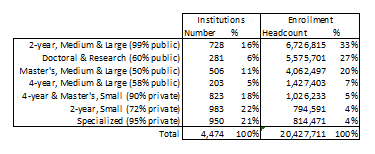

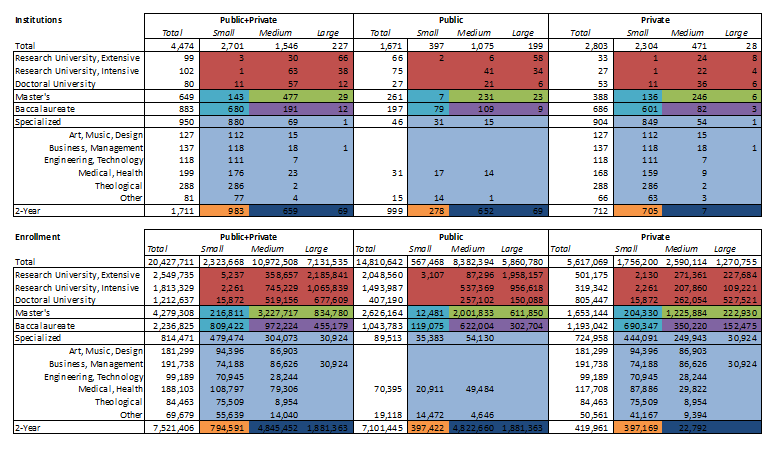

According to the National Association of College Stores (NACS), there are about 4500 bookstores serving US higher education (probably coincidentally, that’s about the number of degree-granting institutions in the US, of which about two thirds are nonspecialized institutions enrolling more than just a few students). Many stores counted by NACS are simply stores near campuses rather than located on or formally associated with them.

According to the National Association of College Stores (NACS), there are about 4500 bookstores serving US higher education (probably coincidentally, that’s about the number of degree-granting institutions in the US, of which about two thirds are nonspecialized institutions enrolling more than just a few students). Many stores counted by NACS are simply stores near campuses rather than located on or formally associated with them.

Of the campus-located, campus-associated stores, over 820 are operated under outsourcing contracts by Follett Higher Education Group and about 600 are operated by Barnes & Noble College Booksellers. Another 140 stores are members of the Independent College Bookstore Association (ICBA), and the remainder — I can’t find a good count — are either independent, campus-operated, or operated by some other entity.

The arrangements for outsourced bookstores vary from campus to campus, but they have some features in common. The most prominent of those is the overall deal, which is generally that in return for some degree of exclusivity or special access granted by the campus, the store pays the campus a fee of some kind. The exclusivity or special access may be confined to textbook adoptions, or it may extend to clothing and other items with the campus logo or to computer hardware and software. The payment to the campus may be negotiated explicitly, or it may be a percentage of sales or profit. Some outsourced stores are in campus-owned buildings and pay rent, some own a building part of which is rented to campus offices or activities, and some are freestanding; the associated space payments further complicate the relationship between outsourced stores and campuses but do not change its fundamental dependence on the exchange of exclusivity for fees.

For the most part outsourcing bookstores seems to serve campuses well. Managing orders, inventories, sales, and returns for textbooks and insignia items requires skill and experience with high-volume, low-margin retail, which campus administrators rarely have. Moreover, until recently bookstore operations generally had little impact on campus operations and vice versa.

Because bookstore operations generally stood apart from academic and programmatic activities on campus, negotiating contracts with bookstores generally emphasized “business” issues. Since these for the most part involved money and space, negotiations and contract approvals often remained on the “business” side of campus administration, along with apparently similar issues like dining halls, fleet maintenance, janitorial service, lab supply, and so forth. Again, this served campuses well: the campus administrators most attuned to operations and finance (chief finance officers, chief administrative officers, heads of auxiliary services) were the right ones to address bookstore issues.

Over the past few years this changed, first gradually and then more abruptly.

Over the past few years this changed, first gradually and then more abruptly.

- First, having bookstores handle hardware and software sales to students (and in some cases departments) came into conflict with campus desires to guide individual choices and maximize support efficiency through standardization and incentives, none of which aligned well with bookstores’ need to maximize profit from IT sales — an important goal, with campus bookstore sales essentially flat since 2005-2006 despite 10%+ enrollment growth.

- Second, the high price of textbooks drew attention as a major component of growing college costs, and campuses sought to regain some control over it — NACS reports that the average student spends $483 on texts and related materials, that the average textbook price rose from $56 in 2006-2007 to $62 in 2009-2010, and that the typical margin on textbooks is about 22% for new texts and 35% for used ones.

- Third, as textbooks have begun to migrate from static paper volumes to interactive electronic form, they have come to resemble software more than sweatshirts in that individual student purchases through bookstores may not be the optimal way to distribute or procure them.

That last point — that bookstores may not be the right medium for selling and buying textbooks — potentially threatens the traditional bookstore model, and therefore the outsourcing industry based on it. Not surprisingly, bookstores have responded aggressively to this threat, both offensively and defensively. On the offensive front (I mean this in the sense “trying to advance”, rather than “trying to offend”), the major bookstore chains have invested in e-reader technology, and have begun experimenting extensively with alternative pricing and delivery models. On the defensive front, they have tried to extend past exclusivity clauses to include electronic texts and other new materials.

Many campuses expressed interest in the EDUCAUSE/Internet2 EText Pilot, going so far as to add themselves to a list, make preliminary commitments, and attend the webinar. Filled with enthusiasm, many webinar attendees began talking up the pilot on their campuses, and many of them then ran into a wall: they learned, often only when they double-checked with their counsel in the final stages of applying, that their bookstore contracts — Barnes & Noble and Follett both — precluded their participation in even a pilot exploration of alternative etext approaches, since the right to distribute electronic textbooks was reserved exclusively for the outsourced bookstore.

The CIO from one campus — I’ll call it Omega University — discovered that a recent renewal of the bookstore contract provided that during the 15-year term of the contract, “the Bookstore shall be the University’s …exclusive seller of all required, recommended or suggested course materials, course packs and tools, as well as materials published or distributed electronically, or sold over the Internet.” The OmegaU CIO was outraged: “In my mind,” he wrote, “the terms exclusive and over the Internet can’t even be in the same sentence! And to restrict faculty use of technology for next 15 years is just insane.”

The CIO from one campus — I’ll call it Omega University — discovered that a recent renewal of the bookstore contract provided that during the 15-year term of the contract, “the Bookstore shall be the University’s …exclusive seller of all required, recommended or suggested course materials, course packs and tools, as well as materials published or distributed electronically, or sold over the Internet.” The OmegaU CIO was outraged: “In my mind,” he wrote, “the terms exclusive and over the Internet can’t even be in the same sentence! And to restrict faculty use of technology for next 15 years is just insane.”

If the last decade has taught us anything, it is that the evolutionary cycle for electronic products is very short, requiring near-constant reappraisal of business models, pricing, and partnerships. That someone on campus signed a contract fixing electronic distribution mechanisms for 15 years may be an extreme case, but we’ve learned even from less pernicious cases that exclusivity arrangements bound to old business models will drastically constrain progress.

And so the ghost’s readiness again yielded raw meat: technological progress translated well-intentioned, longstanding bookstore contracts that had served campuses well into obstacles impeding even the consideration of important changes.

3. So What Do We Do?

It’s important to draw the right inference from all this.

The problem isn’t simply Microsoft trying to lock customers into the Campus Agreement or bookstore operators being avaricious; rather, they’re acting in self-interest, albeit self-interest that in each case is a bit short-sighted.

The compounding problem is that we in higher education often make decisions too narrowly. In the case of the Campus Agreement, we were so focused on the important move from per-copy to site licensing, a major win, that we didn’t pay sufficient negotiating time or effort to the so-called exit clauses — which, in retrospect, could certainly have been written in much less problematic ways still acceptable to Microsoft. In the case of bookstore contracts, we failed to recognize that what had been a distinct, narrow set of activities readily handled within business and finance was being driven by technology into new domains requiring foresight and expertise generally found elsewhere on campus.

Sadly, there’s no simple solution to this problem. It’s hard to take everything into account or involve every possible constituency in a decision and still get it done, and decisions must get done. Perhaps the best solution we can hope for is better, more transparent discussion of both past decisions and future opportunities, so that we learn collectively and openly from our mistakes, take joint responsibility for our shared technological future, and translate accurately back and forth between what we want and what we get.

Today, for example, the rapidly growing capability of small smartphones has taxed previously underused cellular networks. Earlier, excess capability in the wired Internet prompted innovation in major services like

Today, for example, the rapidly growing capability of small smartphones has taxed previously underused cellular networks. Earlier, excess capability in the wired Internet prompted innovation in major services like  Progress, convergence, and integration in information technology have driven dramatic and fundamental change in the information technologies faculty, students, colleges, and universities have. That progress is likely to continue.

Progress, convergence, and integration in information technology have driven dramatic and fundamental change in the information technologies faculty, students, colleges, and universities have. That progress is likely to continue. Everyone – or at least everyone between the ages of, say, 12 and 65 – has at least one authenticated online

Everyone – or at least everyone between the ages of, say, 12 and 65 – has at least one authenticated online  It’s striking how many of these assumptions were invalid even as recently as five years ago. Most of the assumptions were invalid a decade before that (and it’s sobering to remember that the “3M” workstation was a lofty goal as recently as 1980 and cost nearly $10,000 in the mid-1980s, yet today’s

It’s striking how many of these assumptions were invalid even as recently as five years ago. Most of the assumptions were invalid a decade before that (and it’s sobering to remember that the “3M” workstation was a lofty goal as recently as 1980 and cost nearly $10,000 in the mid-1980s, yet today’s  In colleges and universities, as in other organizations, information technology can promote progress by enabling administrative processes to become more efficient and by creating diverse, flexible pathways for communication and collaboration within and across different entities. That’s organizational technology, and although it’s very important, it affects higher education much the way it affects other organizations of comparable size.

In colleges and universities, as in other organizations, information technology can promote progress by enabling administrative processes to become more efficient and by creating diverse, flexible pathways for communication and collaboration within and across different entities. That’s organizational technology, and although it’s very important, it affects higher education much the way it affects other organizations of comparable size. For example, by storing and distributing materials electronically, by enabling lectures and other events to be streamed or recorded, and by providing a medium for one-to-one or collective interactions among faculty and students, IT potentially expedites and extends traditional roles and transactions. Similarly, search engines and network-accessible library and reference materials vastly increase faculty and students access. The effect, although profound, nevertheless falls short of transformational. Chairs outside faculty doors give way to “learning management systems” like

For example, by storing and distributing materials electronically, by enabling lectures and other events to be streamed or recorded, and by providing a medium for one-to-one or collective interactions among faculty and students, IT potentially expedites and extends traditional roles and transactions. Similarly, search engines and network-accessible library and reference materials vastly increase faculty and students access. The effect, although profound, nevertheless falls short of transformational. Chairs outside faculty doors give way to “learning management systems” like  For example, the

For example, the  This most productively involves experience that otherwise might have been unaffordable, dangerous, or otherwise infeasible. Simulated chemistry laboratories and factories were an early example – students could learn to

This most productively involves experience that otherwise might have been unaffordable, dangerous, or otherwise infeasible. Simulated chemistry laboratories and factories were an early example – students could learn to  This is the most controversial application of learning technology – “Why do we need faculty to teach calculus on thousands of different campuses, when it can be taught online by a computer?” – but also one that drives most discussion of how technology might transform higher education. It has emerged especially for disciplines and topics where instructors convey what they know to students through classroom lectures, readings, and tutorials. PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automated Teaching Operations) emerged from the

This is the most controversial application of learning technology – “Why do we need faculty to teach calculus on thousands of different campuses, when it can be taught online by a computer?” – but also one that drives most discussion of how technology might transform higher education. It has emerged especially for disciplines and topics where instructors convey what they know to students through classroom lectures, readings, and tutorials. PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automated Teaching Operations) emerged from the  Sometimes a student gets all four together. For example, MIT marked me even before I enrolled as someone likely to play a role in technology (admission), taught me a great deal about science and engineering generally, electrical engineering in particular, and their social and economic context (instruction), documented through grades based on exams, lab work, and classroom participation that I had mastered (or failed to master) what I’d been taught (certification), and immersed me in an environment wherein data-based argument and rhetoric guided and advanced organizational life, and thereby helped me understand how to work effectively within organizations, groups, and society (socialization).

Sometimes a student gets all four together. For example, MIT marked me even before I enrolled as someone likely to play a role in technology (admission), taught me a great deal about science and engineering generally, electrical engineering in particular, and their social and economic context (instruction), documented through grades based on exams, lab work, and classroom participation that I had mastered (or failed to master) what I’d been taught (certification), and immersed me in an environment wherein data-based argument and rhetoric guided and advanced organizational life, and thereby helped me understand how to work effectively within organizations, groups, and society (socialization). Instruction is an especially fertile domain for technological progress. This is because three trends converge around it:

Instruction is an especially fertile domain for technological progress. This is because three trends converge around it: One problem with such a future is that socialization, a key function of higher education, gets lost. This points the way to one major technology challenge for the future: Developing online mechanisms, for students who are scattered across the nation or the world, that provide something akin to rich classroom and campus interaction. Such interaction is central to the success of, for example, elite liberal-arts colleges and major residential universities. Many advocates of distance education believe that social media such as Facebook groups can provide this socialization, but that potential has yet to be realized.

One problem with such a future is that socialization, a key function of higher education, gets lost. This points the way to one major technology challenge for the future: Developing online mechanisms, for students who are scattered across the nation or the world, that provide something akin to rich classroom and campus interaction. Such interaction is central to the success of, for example, elite liberal-arts colleges and major residential universities. Many advocates of distance education believe that social media such as Facebook groups can provide this socialization, but that potential has yet to be realized. Drivers headed for

Drivers headed for

“There are two possible solutions,” Hercule Poirot says to the assembled suspects in Murder on the Orient Express (that’s p. 304 in

“There are two possible solutions,” Hercule Poirot says to the assembled suspects in Murder on the Orient Express (that’s p. 304 in  The straightforward projection, analogous to Poirot’s simpler solution (an unknown stranger committed the crime, and escaped undetected), stems from projections how institutions themselves might address each of the IT domains as new services and devices become available, especially cloud-based services and consumer-based end-user devices. The core assumptions are that the important loci of decisions are intra-institutional, and that institutions make their own choices to maximize local benefit (or, in the economic terms I mentioned in

The straightforward projection, analogous to Poirot’s simpler solution (an unknown stranger committed the crime, and escaped undetected), stems from projections how institutions themselves might address each of the IT domains as new services and devices become available, especially cloud-based services and consumer-based end-user devices. The core assumptions are that the important loci of decisions are intra-institutional, and that institutions make their own choices to maximize local benefit (or, in the economic terms I mentioned in  One clear consequence of such straightforward evolution is a continuing need for central guidance and management across essentially the current array of IT domains. As I tried to suggest in

One clear consequence of such straightforward evolution is a continuing need for central guidance and management across essentially the current array of IT domains. As I tried to suggest in  If we think about the future unconventionally (as Poirot does in his second solution — spoiler in the last section below!), a somewhat more radical, extra-institutional projection emerges. What if Accenture, McKinsey, and Bain are right, and IT contributes very little to the distinctiveness of institutions — in which case colleges and universities have no business doing IT idiosyncratically or even individually?

If we think about the future unconventionally (as Poirot does in his second solution — spoiler in the last section below!), a somewhat more radical, extra-institutional projection emerges. What if Accenture, McKinsey, and Bain are right, and IT contributes very little to the distinctiveness of institutions — in which case colleges and universities have no business doing IT idiosyncratically or even individually? Despite changes in technology and economics, and some organizational evolution, higher education remains largely hierarchical. Vertically-organized colleges and universities grant degrees based on curricula largely determined internally, curricula largely comprise courses offered by the institution, institutions hire their own faculty to teach their own courses, and students enroll as degree candidates in a particular institution to take the courses that institution offers and thereby earn degrees. As

Despite changes in technology and economics, and some organizational evolution, higher education remains largely hierarchical. Vertically-organized colleges and universities grant degrees based on curricula largely determined internally, curricula largely comprise courses offered by the institution, institutions hire their own faculty to teach their own courses, and students enroll as degree candidates in a particular institution to take the courses that institution offers and thereby earn degrees. As  The first challenge, which is already being widely addressed in colleges, universities, and other entities, is distance education: how to deliver instruction and promote learning effectively at a distance. Some efforts to address this challenge involve extrapolating from current models (many community colleges, “laptop colleges”, and for-profit institutions are examples of this), some involve recycling existing materials (Open CourseWare, and to a large extent the Khan Academy), and some involve experimenting with radically different approaches such as game-based simulation. There has already been considerable success with effective distance education, and more seems likely in the near future.

The first challenge, which is already being widely addressed in colleges, universities, and other entities, is distance education: how to deliver instruction and promote learning effectively at a distance. Some efforts to address this challenge involve extrapolating from current models (many community colleges, “laptop colleges”, and for-profit institutions are examples of this), some involve recycling existing materials (Open CourseWare, and to a large extent the Khan Academy), and some involve experimenting with radically different approaches such as game-based simulation. There has already been considerable success with effective distance education, and more seems likely in the near future. As courses relate to curricula without depending on a particular institution, it becomes possible to imagine divorcing the offering of courses from the awarding of degrees. In this radical, no-longer-vertical future, some institutions might simply sell instruction and other learning resources, while others might concentrate on admitting students to candidacy, vetting their choices of and progress through coursework offered by other institutions, and awarding degrees. (Of course, some might try to continue both instructing and certifying.) To manage all this, it will clearly be necessary to gather, hold, and appraise student records in some shared or central fashion.

As courses relate to curricula without depending on a particular institution, it becomes possible to imagine divorcing the offering of courses from the awarding of degrees. In this radical, no-longer-vertical future, some institutions might simply sell instruction and other learning resources, while others might concentrate on admitting students to candidacy, vetting their choices of and progress through coursework offered by other institutions, and awarding degrees. (Of course, some might try to continue both instructing and certifying.) To manage all this, it will clearly be necessary to gather, hold, and appraise student records in some shared or central fashion. Poirot’s second solution to the Ratchett murder (everyone including the butler did it) requires astonishing and improbable synchronicity among a large number of widely dispersed individuals. That’s fine for a mystery novel, but rarely works out in real life.

Poirot’s second solution to the Ratchett murder (everyone including the butler did it) requires astonishing and improbable synchronicity among a large number of widely dispersed individuals. That’s fine for a mystery novel, but rarely works out in real life. Back in 1977,

Back in 1977,  Higher education traditionally has placed a high value on institutional individuality. Some years back a Harvard faculty colleague of mine,

Higher education traditionally has placed a high value on institutional individuality. Some years back a Harvard faculty colleague of mine,  At the same time, it has failed to make the critical distinction between what

At the same time, it has failed to make the critical distinction between what  The dilemma is this:

The dilemma is this: And so the $64 question: What would break this cycle? The answer is simple: sharing information, and committing to joint action. If the prisoners could communicate before deciding whether to defect or cooperate, their rational choice would be to cooperate. If colleges shared information about their plans and their deals, the likelihood of effective joint action would increase sharply. That would be good for the colleges and not so good for the vendor. From this perspective, it’s clear why non-disclosure clauses are so common in vendor contracts.

And so the $64 question: What would break this cycle? The answer is simple: sharing information, and committing to joint action. If the prisoners could communicate before deciding whether to defect or cooperate, their rational choice would be to cooperate. If colleges shared information about their plans and their deals, the likelihood of effective joint action would increase sharply. That would be good for the colleges and not so good for the vendor. From this perspective, it’s clear why non-disclosure clauses are so common in vendor contracts.