The Information Center (MIT, 1969)

(My MIT 50th reunion this year, albeit likely to cancel. Anyway, thinking back. And then ran across something interesting. In January 1970, I had a 21.07 paper due, and was having trouble with it. I was also thinking about the intense fall of 1969, including the Moratorium, the November Actions, and the Information Center that arose to help MIT cope with the latter. I’d spent endless hours working in the Information Center, and that somehow seemed important. Aha! Paper topic! The result was unlike anything I’d ever written before and not quite consistent with the assignment, which Roy Lamson, my professor, remarked mildly while nevertheless giving me an A. Looking for something else, I just found the paper, slightly yellowed on its Corrasable Bond. Rereading it, I thought it might interest others–there’s lots in it, I think, that fits 2020. Looking back, it may well be this paper that gave my career its final push toward higher education policy and leadership rather than engineering… )

LISTEN use microphones not loudspeakers read don’t write take a leaflet someday “It is a dynamic…” no static.

The University exists so that there may be somewhere a place for the courageous and direct confrontation of ideas

whereas recent history has been marked by violent confrontations, which escalated out of proportion because of the failure of those academic communities to act in a responsive way

we express our contempt for this injunction by counselling and advising all mit students to participate

MIT plans a takeover of Black Community confirmed count for number of demonstrators is three hundred sixty five count for police is two hundred sixteen

the problems of these times are not simple and will not yield to simple solutions of any kind

Earth could be fair and you and I must be free.

All of which is not me, but others speaking and writing but which I put together to show that anything you read can make sense if you want it to even if it actually doesn’t.

I was, to make this an at least partially significant paper, going to devise some guidelines for the future, guidelines to prevent the recurrence of a situation where the majority of people concerned are but a mere minority of the whole. I was going to predict that, if trust did not replace assertiveness as a policy, there would be more less rational confrontations, and that reestablishment of trust was the only way to prevent these. I was going to argue, at length, that the processes by which the Institute reaches decisions must be modified to conform to the interest in and effect of the particular decision.

When I returned from Christmas vacation, where I had defended MIT’s fairness to my parents and friends, Mike Albert had been expelled. What could I do? Write an “I told you so”? My outline went by the wayside. I wrote, instead, directly from my feelings and from my documents; from my friends, and from my and their frustration. If the result is at times incoherent, it is because its subject is increasingly incoherent. If it leads no where…

well, where is it all going, anyhow?

We never really worried about it until it was time to close up and go home—and we wouldn’t have then, only we had to put something on the door to tell people why we weren’t there anymore. Kind of a loyalty to one’s fans, or listeners, or whoever. The problem was that some of us had read a significance into our existence—even the mere fact of it. For us to close meant something—it suggested that things had changed, or changed and unchanged, or something like that.

Then we started thinking up possible signs. Marv wanted it to tell people to use each other, I wanted it to tell people to continue their curiosity, Laddie wanted a peace symbol. We worked up a one page statement, about the trust that must be inherent in a community, even when it is faced with abnormal conditions. We put that one up, and then took it down. We weren’t supposed to be editorializing, just reporting. Yet we needed something.

The need for communication never ceases

You trusted us, now trust each other

The Information Center has closed. Peace.

and so it came to an end—-or we hoped a beginning. But of what? It was nothing really easily expressible—we weren’t doing just one easily identifiable thing. It wasn’t us doing anything, actually, that did any good; it was what people did because of or in spite of us.

But we must begin! First, of course, we must discover what was happening that let all this happen.

The Instrumentation Laboratory is a direct descendant of the work on gunfire control begun during World War II by Professor Draper; in fact, the Laboratory has been continuously guided, by the genius of Professor Draper, its first and current Director. It is an advanced, technology laboratory devoted primarily to vehicle guidance and control, largely for space and military applications.

The Pounds Commission Report

A central issue of the seventies for defense research is the double threat of, first, an unwholesome alienation of the university community from national defense research and, second, a diversion of essential research funds from their intended purpose.

John S. Poster Jr., DOD research director.

Second, I would like very much to see our work in basic technology related to defense continue—and I do believe that it is important to the future of this country that such work continue. I intend to ask the Department of Defense for a substantial fund for the support of basic technology related to defense.

Howard Johnson

The term “defense” is a euphemism. U.S. “defense** weapons are being used in Vietnam. 3500 U.S. “defense” bases exist in 38 countries. More than one million members of U.S. “defense” forces are scattered around the world. “Defense” research at M.I.T. supports these activities.

New University Conference pamphlet

The Helicopter project goes on. MIRV goes on. MTI goes on. ABM goes on. CAM goes on. COMCOM goes on. And the International Communism project goes on. And as the meaningless committees meet, the war in Vietnam goes on. Vietnamese die and victims of U.S. Imperialism around the world suffer in part through the effort of M.I.T.

On November we will come to M.I.T. to stop these projects. Through militant action we will start a struggle to ultimately destroy imperialism.

November Action Coalition leaflet

The threats we have been hearing recently constitute the most dangerous attack of such basic freedoms of individuals on this campus. The pluralism that is the heart of the university cannot survive for very long in such a climate…We cannot allow free access and free expression to be obstructed…! simply say that any acts by individuals or groups that coerce other individuals and groups from speaking and acting freely I consider to be fascist tactics..But if such threats continue to be made and if it appears that such action will materialize, I would feel it necessary to call uptn the civil authorities for help in advance of the carrying out of such explicit threats to burn, to break, to push, or to stop.

Howard Johnson

The demonstrations at MIT are not meant to be the violent acts of a heroic few. They are to be political attacks on the projects by large numbers of people. While we will defend ourselves, our objectives are to end these projects, not fight with cops…we will try to fight back as intelligently as possible, seeking to avoid massacres, mass injuries, or arrests. We will not attack MIT students, staff, or professors. Our goal is to stop violence…

NAC leaflet

Certain members of the respondent NAC have announced that the above actions will be carried out despite the efforts of your petitioner to prohibit them. The petitioner understands the respondents statements to mean that the respondents and those acting with them will use such force as is necessary to accomplish the actions listed above…The petitioner says that the threatened actions and occupation by the repondents a will create circumstances in which disruption,’damage, and injury are almost certain to occur, all to the irreparable harm of the petitioner, its faculty, staff, and students…

Petition for the Temporary Restraining Order.

We used to talk in the halls, greet one another—but now, for the last month, Mike hasn’t even smiled, and George doesn’t drop in anymore.

coalesced statements of various Deans and Provosts

In the meantime, until such hearing, WE COMMAND YOU, … to desist and refrain from (a) employing force or violence.. (b)damaging or defacing facilities… (c) converting without authorization, files… (d) inciting or counselling others to do any of the above-mentioned acts.

the Temporary Restraining Order

so the cards were on the table, but NAC was at the Student Center and the Administration was in 9-350 and 351, and nobody connected them, and they stood to themselves, and it was Monday, and one pm.

people talking without speaking

people hearing without listening

people writing songs that voices never shared

no one dared

disturb the sounds of silence.

To members of the MIT community:

NOTICE

Through the efforts of an ad. hoc group of members of the MIT community, a special Information Center will be established in the Bush Room…the Center, which will be maintained during the first part of the week, will be open on subsequent days from 8:00 am to 12:00 midnight. It may be reached also via Institute telephone extension 1874 during these times.

the Notice

Ah yes! 1874, and its friends 1875, 6, 7, and 8. Later, of course, they were joined by three dorm lines, and occasional walkie talkie and shouting networks. We put them all on a giant round table, with pads and leaflets and lists and statements, in front of the Board. The four television sets were distributed about the room, one on each major network for news coverage. The radios, on various stations, went continuously, and we tried to absorb it all.

The Board—later expanded to three—was the thing we really took care of. Nothing went on it without double verification. We put up meeting times, places, and rules; we illustrated briefings; we noted major rumors and their validity; we tried to put a statement of NOW. We covered the walls with background: leaflets, counter-leaflets, speeches, statements, clippings, and eventually photographs. We made copies of everything we could, and soon started our own set of news releases. The external news media occasionally dropped in, but for some reason didn’t like us. Maybe the disparity between their versions and ours bothered them. Maybe it was because we didn’t like them. Who knows?

Nine or ten people sat around, the table, answering phones and doing the calling required to verify things. All sorts of people got calls from us: the ticket agent at the Orson Welles Cinema, at Central Square, a secretary in the Harvard Trust’s Kendall Square office, and many more. Anyone else in the room manned the tables that held all of our printed and Xeroxed material, mostly to explain, answer, and interpret. All sorts of people worked: rabid anti-SDSers, apathetic tools, student government people, and pro-NAC people. We did not refrain from expressing our personal views, but when asked for fact we distributed only our verified fact.

20:50 Ron Schmid, Kasser, Milloid from USL in E40 called and claimed 1) phone company is installing special bypass equipment on threatened buildings 2) Police and National Guard are mobilizing to occupy MIT at 2:00 am. Heard from phone company employee.

21:00 Harvey Baker, TECH, called. Cambridge police are to move into MIT tonight, stay all night.

21:05 called Martin Berlan, communications, re phone rumor, not home yet, left message.

21:06 Brian, TECH, called, we asked for help (go and see) back up or quash mobilization rumor

21:14 Brian called, found no basis for rumor.

21:18 Relayed above to Thursday s

21:30 Martin Berlan called, no basis to phone rumor

21:45 Ed came back from checking Cambridge Police Headquarters and State barracks and Armory. No activity. Only one police car, #204, with four cops, seen

The Log, page 22, 3 November 19&9, edited.

This is what most of the work in the passive phase was all about: hear a rumor, check it out, post and circulate the information. It was occasionally challenging, kept us sufficiently busy. A lot of rumors were flying, and we managed to get the facts to a large number of people.

But I said passive phase, which is eventually the key to the puzzle, for it was during the active phase that we worried about why we had to exist and became a bit disturbed. The active phase was when we started finding things out before they happened, when we started going to meetings, when we started, in the field of information, taking action. But we’re not ready for that part yet. We haven’t accounted 1 for the passive.

During the week of November 3, it will be important that members of the community be able to obtain both accurate and exhaustive information on events that are occurring on the campus.

the Notice

But isn’t it always important? After all, isn’t one of the things that somehow makes the MIT community special? Ease of communication has always been a feature of MIT. Professors are available for talk and consultation, there is a congenial Dean’s office, and a good set of shrinks. Even Howard Johnson walks the halls, greeting people and occasionally stopping to talk. Faculty meetings and committees have been, to varying degrees, open to observation and participation by interested people. There is usually an air of openness.

Usually. This brings us back to earth, and to a starting point for a discussion of the meaning of the Information Center. It should be noted that, with respect to the actions and. their aftermath, I am a cynic. I quote the Los Angeles Times:

A week ago at MIT, because the expected violence did not occur, both radical leaders and administrators were gradually claiming victory.

Los Angeles Times, 13 Nov 1969

This statement was partly in jest, but it was in a sense true. The point is that the NAC and the Administration were fighting two different battles, without actually ever realizing it. The result was bound to be favorable in some way for each side, but in all likelihood nothing would have been accomplished towards ending either battle. But back to the Center.

The Information Center should not have been needed. If all had been right, as in the past, there would have been no need for people to find what was, in the words of the Corporation Joint Advisory Committee on Institute-wide affairs (CJAC)”an unbiased group…to disseminate facts”. They should have been able to use their normal sources, whatever they might have been. For some reason, however, people had stopped listening to what was being said to them.

But my words like silent raindrops fell

echoed in the wells of silence

and the people bowed and prayed

to the neon gods they’d made

as the sign flashed out its warning

There is an explanation of this, that may or may not apply. People tend to listen to what concerns or interests them, and become disturbed when this information is withheld from them. The early roots of the November Actions, all the way back to the March 4 research stoppage and the Agenda Days, were listened to if not supported by most people at MIT. Gradually, those who did not agree with or care about the problems presented ceased listening to anything related to them. The groundwork of the November Actions—the presentation of them, if you will—went unheeded. As the NAC gradually evolved its plans, and as the Administration made its early warning statements, most people were unaware of anything abnormal. When action was finally imminent, and overshadowed many normal activities, these same people suddenly discovered the whole situation for the first time. They became disturbed, since they felt they had not been told of it. This disturbance produced a mistrust of the agencies they normally would have relied on for Information, and caused them to seek a new source that could tell them what was really happening.

Given such curiosity, these people were likely to look only until they found some source that they did not already mistrust. This could be anything: the media, or a friend, or anything. It is in this sort of situation that the spread of a rumor is facilitated enough for it to cause action unwarranted by the facts, and it was in this sort of situation that the Information Center was introduced as a reliable and available source.

The Center had, of course, to establish itself. We were completely independent, which was the first step. The second and more critical step was to exercise this independence and provide unbiased reliable information. This was easier than we thought it would be. We used the technique of overkill, of massive cross-checking of facts. The volume of calls received, even the first afternoon, was large, and soon the Center seemed to be performing its assigned task well. After one briefing, we were accused of slanting facts in favor of the NAC—and, by a different person, in favor of the Administration. This was heartening.

The role of the Information Center was thus initially a passive one: given an inquiry, it investigated; given a rumor, it tried to back or quash it; given a statement, it disseminated it. There was no effort to go beyond this role, no active seeking of information, no attempt to prevent the origin of rumors. This role lasted until Monday night, when events caused a change, but a few further words first.

Work at the Information Center was on an entirely open and voluntary basis. There was a core of about ten people who worked consistently, a few of these actually working an average of eighteen or twenty hours a day. The work was often frustrating, for we with some regularity were placed in the position of spokesmen for everyone at once. At the same time, we began to feel the effects of passivity: we got behind the action; we were often unable to answer questions about what was supposed or going to happen; our “over the table” discussions were increasingly unable to answer the “why?” questions we were getting. Finally, despite claims to the contrary, we felt that we were not being given much of the information that we should have been getting, both from the Administration and the NAC. The event that finally changed this was the release of the police policies for the I-Lab confrontation. The CJAC report:

Late in the afternoon of November 5 (the day before the NAC/police confrontations at I-Lab) a statement was released by Cambridge City Manager Sullivan as to the police guidelines which would be used in the event that police were needed.

This would have been perfect, if it were the truth. This statement was formulated, but not released, that afternoon. We became aware of its existence and contents through a member of the Student Advisory Group. Several of us felt that its release could considerably help to prevent undue violence the next day, since it suggested quite a departure from the police action that was expected on the basis of past experience. We therefore wrote it up and released it to the NAC, THE TECH, Thursday, and WTBS about 10 pm. Several members of the administration, when apprised of this fact, were angry and attempted to limit its spread. After some negotiation, a slightly edited version was released to anyone who wanted it. The actual Public Relations release is dated November 5 (and is, interestingly enough, the unedited version).

Sow, and ye shall reap

Galatians 6:7 (paraphrased)

Seek, and ye shall find.

The person who took a copy of the release to the NAC meeting stayed at the meeting and, through periodic reports, made it possible for us to predict what would occur. The NAC did not object to our discussing their objectives and reasons publicly; in fact, they felt that it aided them. The Administration, who had been excluded from the meetings, were also able to know what to expect. They also began to tell us—for release—what their feelings were as to what administration response would be to this or that eventuality. The Board was soon covered with statements of intent and policy from both sides, random facts being relegated to two new boards. More and more people who came in to inquire about something were encouraged to go participate or observe as a better means of informing themselves. We set up what almost amounted to an intelligence system, which kept us truly up to date. We had gone active.

The active phase, which lasted until we closed, was an attempt to, in various ways, reestablish channels of information independent of us. The Information Center, in the passive phase, filled a void, but it did nothing to prevent the recurrence of the void when it might close. We advocated, in the active phase, interest in what was going on, and not support for either side. At various times we were visited by representatives of NAC, SACC, or the Administration, which usually produced discussion in the room. This was good.

The Information Center may or may not have helped make the November Actions what they were. Its effect, however, was supposed to transcend the particular moment and perhaps reestablish trust.

Fools, said I, you cannot know

silence like a cancer grows

heed my words and I might teach you

You trusted us

now trust one another.

It didn’t work. Why is hard if not impossible to say. Perhaps we should have had one after the actions, an Information Center about information. God only knows, and he ain’t saying. The point is, when people look back at the Actions now they see them as an isolated event, with nothing before them and nothing after. The CJAC report spends much of its time on the question of “enfranchising” everyone, of giving them the opportunity and knowledge to “plugin” to the system where they feel they can do the most. It asks

How do you begin to establish trust among different people an campus? Is there a “credibility gap”? Will actions have to precede words?

Such questions, just before the Actions, produced the Information Center. The fact that they are still being asked, and that they are equally as far from an answer, indicates that perhaps nothing has changed. The report says

That the November Actions passed without a major rift in the MIT Community has allayed many of these concerns …

but this is not reassuring. There is no more of a rift now than there was before the actions, but that speaks for itself. Undoubtedly there will be many more reports, evaluations, and analyses of the Actions. The facts remain—for a while, there was effective interaction of students and faculty, but it has gone. There was immediacy about many issues, but it has gone. There was communication and trust, but it, too, has gone.

We need them back.

One suggestion is to have another set of Actions of a similar sort, e.g., addressed to a very broad set of issues. The suggestion is not a facetious one; something like the Moratoria would qualify. Of course, the crisis effect, which is what is needed, is lost if the action is too popular and unthreatening. There is, on the other hand, the alienation effect which works against us.

We must dispense, therefore, with the idea of using actions and confrontation to produce the effects we want. The action approach, however, when analyzed, yields a lesson: that of immediacy. The opposite, the feeling of change and reaction taking forever, is well known: it was the chief way the leaders of NAC were able to make sure they had truly dedicated people voting, since everyone else would leave if the meeting dragged on too long. The endless commission and committee approach produces similar reduction of interest. This effect, whether intended or not, works against our desires. It must be replaced by a sense of immediacy.

ONE: Immediacy

We then proceed to the question of polarization.

Everyone at MIT likes to feel that he matters, that he is part of things, that the policies which affect him have in some way been affected by him. It is for this reason that so many things are brought before the faculty for decision; it is for this reason there are students on committees. If one is not in either of these two categories, however, there are but two choices: he can ignore (or “not care about”) the places where he has no voice, or he can make or join an organization which offers him such a voice. The first of these produces the famous MIT apathy; the second produces radical action from outside the normal system structure or, in short, polarization. The lesson is again clear (and this is not a novel idea): broaden the base of the decision process so as to, at the proper time, include all of those affected by the policy or act in question. .

ONE: immediacy

TWO: involvement

And then there is the question of integrity, of consistency, of respect. The NAC and the administration both were consistent throughout the actions, and thus each was listened to to a fair degree. Had the NAC not stood by its intentions, but instead gone, say, lab-smashing, it would have lost much of its support from outside itself and, more important, its respect from the administration. In the same way, the administration had to stick to its intentions, or it could not have faulted the NAC for smashing. This admirable behavior has ceased, with the ignoring of the report of the Inside Action committee on disciplinary recommendations by the Administration and the irrational response of the RLSDS and their supporters.

ONE: immediacy

TWO: involvement

THREE: Integrity

The Information Center, given the first condition, added the latter two. There is no reason that it has to exist for this to occur.

I was going to make a case for following the suggestions actively so as to channel activity into constructive means for solving problems. I wanted this to be taken as more than a purely academic exercise.

But it is one. The case has gone moot on me, rejected before its presentation.

frus.tra.tion, n.2: a deep chronic sense or state of insecurity and dissatisfaction arising from unresolved problems.

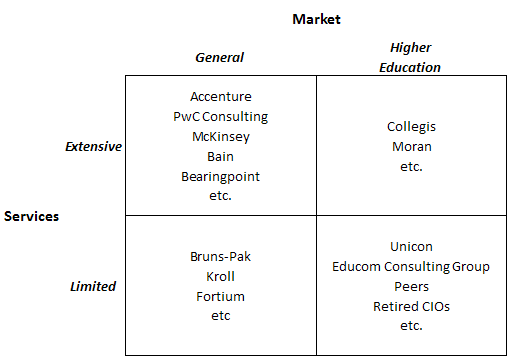

On the informal agenda, a bunch of us work behind the scenes trying to persuade two existing higher-education IT entities–

On the informal agenda, a bunch of us work behind the scenes trying to persuade two existing higher-education IT entities–

Most everyone appears to agree that having two competing national networking organizations for higher education wastes scarce resources and constrains progress. But both NLR and Internet2 want to run the consolidated entity. Also, there are some personalities involved. Our work behind the scenes is mostly shuttle diplomacy involving successively more complex drafts of charter and bylaws for a merged networking entity.

Most everyone appears to agree that having two competing national networking organizations for higher education wastes scarce resources and constrains progress. But both NLR and Internet2 want to run the consolidated entity. Also, there are some personalities involved. Our work behind the scenes is mostly shuttle diplomacy involving successively more complex drafts of charter and bylaws for a merged networking entity.